National Freight Strategy Framework

Section IV: Strategies and Future Considerations

The draft Plan offered strategies to address the infrastructure, institutional, and financial bottlenecks impeding the safe and efficient movement of goods. The Strategies offered in the draft Plan ranged from the very large, such as creating large discretionary and formula funding programs dedicated to freight projects, to the more narrowly focused, such as to codify a multimodal National Freight Policy. All of these strategies are relevant to the FAST Act's National Multimodal Freight Policy goals, and many of the strategies identified in the draft Plan were implemented in whole or part by the FAST Act. Whereas the draft Plan offered three broad categories of strategies organized around addressing infrastructure, institutional, and financial bottlenecks, we suggest that a new, fourth category be considered for the next Plan that would consolidate the elements of safety, community impacts, and the environment previously treated under infrastructure and institutional bottlenecks, giving these critical subjects more prominence. DOT received substantial public comment on the draft Plan and this proposed category of strategies was highlighted by many commenters as an area needing greater attention in the final Plan. While we again acknowledge that the responsibility for finalizing the National Freight Strategic Plan will fall to the next Administration, it is our hope that the ideas offered here can help guide Federal policymakers and their public and private partners in continuing to move freight policy forward.

Accordingly, the strategies in the new Plan could be organized into the following four categories:

|

|

|

|

As noted, of the strategies and initiatives outlined in the draft Plan, several were addressed in whole or in part by the FAST Act, including through the provision of funding, linkage of some committed formula funding to a State Freight Plan, and other programs. However, some are still unresolved and bear repeating to help our nation prepare for the challenges of an unknown future. In particular, strategies and initiatives that we feel should be expanded or developed more thoroughly are:

- Improve the safety, security, and resilience of the freight transportation system. Ensuring the safety, security, and resilience of freight transportation is of paramount concern to the DOT. In addition to the primary importance of ensuring the safety of human life, a safe, secure, and resilient freight transportation system is less prone to traffic disruptions caused by crashes or infrastructure failures resulting from natural and man-made disasters. Depending on their nature and extent, these disruptions could be short-term and local in scope, or have longer-term repercussions over a regional or national scale. To support this need, DOT is implementing and enforcing safety regulations to address driver fatigue, vehicle stability systems, and transportation of hazardous liquids (including its recent final rule governing the transportation of flammable liquids by rail). DOT could also consider new regulations to replace and improve outdated freight vehicle operating safety rules. DOT will continue to work with the Departments of Homeland Security and Defense, and other Federal partners, to assure the security of the transportation system, including in the growing area of cybersecurity as systems become more automated. In addition, DOT is pursuing strategies to include infrastructure vulnerability and resilience assessments as part of long-range planning efforts.

- Mitigate impacts of freight projects/movements on communities. Safe, secure, and environmentally friendly freight movement is vital to the well-being of communities across the nation and helps ensure the efficient movement of goods that support our economy. Unless properly mitigated, freight movements may impose adverse impacts such as air, water, and noise pollution, and diminished access to jobs, healthcare, and education that can reduce the quality of life for people living in communities adjacent to or isolated by these movements. Community opposition to the potential adverse effects of freight transportation can also impede implementation unless the needs of communities are carefully considered during freight transportation project planning, environmental review, and state permitting or approvals. DOT is working closely with numerous partners, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to continue to reduce the adverse impacts of freight activities. Collaborative efforts include providing funds to reduce air pollution and traffic congestion caused by freight vehicles, supporting research on less impactful freight technologies and delivery systems, and efforts to facilitate freight project planning and implementation.

- Support research and promote adoption of new technologies and best practices. Identifying and applying technologies, as well as sharing best practices, are extremely important in ensuring the safe and efficient movement of goods. For example, FHWA's EDC program has been highly effective in identifying and deploying innovations aimed at shortening project delivery, enhancing the safety of roadways, and protecting the environment. Congress should re-establish the successful, multimodal National Cooperative Freight Research Program (NCFRP) as proposed in the draft Plan and other proposals. NCFRP focused on research to inform investment and operations decisions for improving the nation's freight transportation system performance. Additional resources should be provided to ensure comprehensive federal oversight of emerging technologies,

In addition to the Strategies provided above, we suggest that the next Plan and future legislation should strive to address the following:

- Reduce the confusion, constraints and workload burden on the private sector, States and MPOs relating to national freight mapping initiatives – Multiple stakeholders have noted that having two freight networks (the National Highway Freight Network required under 23 U.S.C. 167 and the National Multimodal Freight Network (NMFN) required under 49 U.S.C. 70103) are confusing and potentially contradictory. In order to reduce this confusion and provide clarity, one multimodal map, sufficiently large to encompass the vast network of supply chains and last-mile/first-mile intermodal connectors that make up the interdependent U.S. freight transportation system, should be retained. This map would be used for planning purposes and all other freight maps and attendant eligibility requirements would be retired. DOT is in the process of issuing such a map in compliance with the FAST Act, which requires the development of a NMFN under 49 USC Section 70103. The NMFN replaces the Multimodal Freight Network map included with the draft Plan.

Develop, foster, and implement environmental initiatives – One goal in the National Multimodal Freight Policy of the FAST Act is to reduce the adverse environmental impacts of freight movement on the National Multimodal Freight Network. In addition to the strategies in the draft Plan (including use of CMAQ funding for freight; low emission technologies for federally funded freight projects), the next Plan could propose programmatic adjustments and policy and legislative strategies to foster environmentally beneficial changes such as: implementing guidance to include greenhouse gas emissions in the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) so that new projects requiring NEPA review can perform a greenhouse gas impact analysis; and reducing pipeline leakage through regulatory actions, improved distribution practices, technology development, and evaluating methods to enhance public involvement in the NEPA process for proposed activities.

Other priorities could include supporting freight congestion mitigation through NHFP formula and CMAQ funding; reduce barriers to truck rest stop electrification; incentivize the use of hybrid and electric freight vehicles, especially in alt-fuel corridors and urban and dense suburban delivery areas; incentivize CNG use by locomotives; improve energy savings in freight facilities; optimize truck movements through expanded use of the Freight Advanced Traveler Information System (FRATIS)1 and other algorithms incorporating multiple data sets for maximum efficiency and reduced fuel consumption or emissions; develop truck parking facilities closer to where truck parking is needed; develop better port, airport and intermodal rail facility plans to reduce congestion, modal repositioning, dwell times and delay.

The freight and environment nexus is one that DOT, working with EPA and other Federal partners, can more fully develop to reduce adverse impacts on our communities and natural environment. This area would benefit from a strong new emphasis at the Federal level, especially where it will also yield reductions or elimination of road, rail, port and airport congestion, fuel consumption and emissions, unnecessary truck VMT, excessive idling, truck parking and staging on neighborhood streets, and dwell times for all modes.

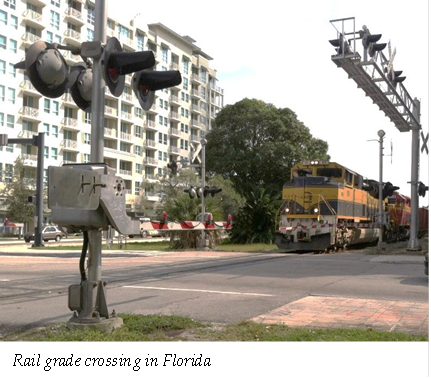

Prioritize public and private investment by applying a multimodal supply-chain, end-to-end analytical framework that will focus on reducing congestion and other challenges facing our nation – As part of an internationally connected system of systems, freight carriers move goods between the nation's regions and the world. The airports and airways, maritime and inland ports, and pipeline systems work with rail yards, distribution centers, and other multimodal hubs to transfer the goods between these systems. By taking an end-to-end supply chain approach to analyzing and funding the freight transportation network at a national and regional level, the Federal government can help to better integrate the freight system by creating operational incentives or funding infrastructure that is a low priority for individual systems but has a large impact on the efficiency of the overall system. These actions can include incentives to align operating hours for ports, truck, rail, and distribution centers;2 funding for short-distance marine highway and rail services that can reduce congestion on crowded surface roadways; eliminating at-grade rail or highway crossings that present significant safety, efficiency, or Ladders of Opportunity impediments; and raising bridges to reduce air-draft restrictions for maritime operators.

-

Integrate multimodal infrastructure within the system and eliminate systemic bottlenecks at intermodal connection points -- Focus funding on the construction and maintenance of intermodal connectors and first- and last-mile road and rail lines that connect freight hubs (maritime ports, rail yards, freight airports and distribution centers) to the interstate highways, Class I railroads, and river/intracoastal maritime networks, as well as for the multimodal infrastructure (port and rail yard) that ties those systems together. In many cases, these connectors and the multimodal infrastructure are not funding priorities for their regions or have limited eligibility for Federal funding programs. This should also include priority funding for secondary infrastructure that is necessary for the smooth operations of these first and last mile networks and multimodal infrastructure, such as truck parking, truck staging, equipment pools, and barge fleeting areas. Integration of multimodal infrastructure must minimize or avoid having an adverse effect on the movement of people through the various transportation modes.

-

Incentivize multimodal infrastructure, corridor and system planning -- Congress could authorize new Federal grants for planning activities (perhaps at reduced non-federal matching levels) to generate more comprehensive freight planning that engages individual public sector agencies (such as ports and toll authorities), together with MPOs, States, and multi-state planning organizations seeking to plan their freight system of the future, including through State Freight Plans and National Freight Advisory Committees. Other Federal agencies outside of DOT should be encouraged to participate in these planning projects or help develop the incentive structure to do planning. Numerous agencies, such as the USACE or agencies in the DOE, as well as the EPA, undertake and provide funding for port and infrastructure planning and development, and without their participation, the goals of such a comprehensive multimodal program would not be fully achievable. With incentives for complex planning activities, there may be a beneficial shift in future planning projects away from responding to individual bottlenecks or choke points or undertaking single-mode fixes, toward regional or multimodal solutions. Such expanded approaches could address corridors that experience sustained systemic congestion, using a mix of infrastructure spending and operational solutions to help alter the flow of freight to reduce congestion, air emissions, and other impacts on the surrounding communities.

-

Expand multimodal flexibility -- One of the greatest game-changing shifts in Federal funding for freight came with the ban on transportation project earmarks initiated by Congress in 2011 and the transportation funding teed up by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), including through the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) discretionary grant program. Because ARRA and subsequent rounds of the TIGER program were funded with General Fund monies, they did not come with the modal stovepipes of previous funding sources. The competitive TIGER program has allowed the public and private sectors to team up on projects that with corridor-level multimodal impacts, such as rail/highway grade separations, intermodal facilities, and landside port improvements. The successes afforded by the TIGER program are evident across the country, and the public investment has leveraged billions of dollars in matching funds from other public and private sector contributions. The requirement that grant requests be accompanied by indicators of their impact on performance and overall net benefits rounded out this responsible new way of improving the transportation assets of this nation. Such innovative project development, selection and award processes should be continued. Under INFRA, eligible applicants can submit cost-effective freight and highway projects for competitive selection to the Federal government. Under NHFP, States can target Federal formula monies to highway and freight projects included in their State Freight Plans and other required State planning documents, including projects within ports and rail facilities.

The major impediments to long term success of these programs are likely to be the limitations on freight investments, particularly on multimodal ones. Given the high demand for freight project funding (one State alone has identified more than $130 billion in unmet freight needs for all types, highway and non-highway, in its State Freight Plan), it would appear unlikely that the needs of the current multimodal network can be accommodated through these programs, even if limited to investments that generate only public benefits. Similarly, the additional limitations on funding eligible port and rail intermodal facilities under the INFRA and NHFP programs reduce our ability to make highly beneficial investments in those facilities. We believe that the efficacy of these programs would benefit from relief from their caps on non-highway investment, as well as higher overall funding authorizations for all freight projects.

For maximum public benefit, the investment amounts should be driven by multimodal State Freight Plans and their associated Freight Investment Plans, informed by engagement of a multimodal State Freight Advisory Committee. Adequate program funding will also be needed, above current levels, to address the daunting backlog of projects affecting the safety and efficiency of the nation's freight system.

Encourage multimodal solutions to address performance issues -- Performance measures for freight were a requirement of MAP-21, albeit confined to consideration of the Interstate System. The rulemaking process for these measures has involved extensive input from States and transportation policy groups. In looking to the future, successful strategies in measuring freight performance should be flexibly defined to include identification and implementation of solutions on adjacent corridors or alternative modes of transportation to keep our nation's commercial corridors vibrant and allow them to evolve with the emerging technologies. Similarly, we suggest that future legislation should require the existence and active participation of a State Freight Advisory Committee to ensure public and private sector dialogue on multimodal issues, planning, and investment in solutions in a manner consistent with the role described in DOT's October 2016 guidance on State Freight Plans and State Freight Advisory Committees.

1 FRATIS is a bundle of applications that provides freight-specific dynamic travel planning and performance information and optimizes drayage operations so that load movements are coordinated between freight facilities to reduce empty-load trips. Return to section containing footnote 1

2 Maritime ports often have limited gate hours. Extending those hours can reduce wait times for trucks accessing the ports, but must be supported by corresponding shifts in the operating times for nearby distribution centers and rail facilities. Return to section containing footnote 2