Responses to the Freight Challenge

Freight has moved to the forefront of many debates and plans concerning transportation in recent years. Stakeholders increasingly express concern that piecemeal improvements to the freight transportation system are not enough. The freight challenge requires a wide range of activities by the private sector and all levels of government that may be organized formally or informally to pursue common objectives.

To better understand the freight challenge and activities conducted by both the private sector and all levels of government, the Transportation Research Board convened the Freight Transportation Industry Roundtable. Comprised of individuals from transportation providers, shippers, state agencies, port authorities, and the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), the Roundtable developed an initial Framework for a National Freight Policy to identify freight activities and focus those activities toward common objectives (Table 5, see page 30).

| OBJECTIVES | STRATEGIES |

|---|---|

| Improve the operations of the existing freight transportation system. | Improve management and operations of existing facilities. Maintain and preserve existing infrastructure. Explore opportunities for privatization. Ensure the availability of a skilled labor pool sufficient to meet transportation needs. |

| Add physical capacity to the freight transportation system in places where investment makes economic sense. | Provide physical access to interstate commerce. Facilitate regionally-based solutions for nationally significant freight corridors and major gateways. Utilize and promote new/expanded financing tools to incentivize private sector investment in transportation projects. |

| Better align all costs and benefits among parties affected by the freight system to improve productivity. | Utilize public sector pricing tools. Utilize private sector pricing tools. Spend public revenues raised from transportation on transportation. Explore opportunities for public-private partnerships and/or privatization. Track progress of performance measured at system and program levels. Ensure benefit-cost analysis and informed decision making are enacted at system and program levels. |

| Reduce or remove statutory, regulatory, and institutional barriers to improved freight transportation performance. | Identify/inventory potential statutory, regulatory, and institutional changes. Provide pilot projects with temporary relief from unnecessarily restrictive regulations and/or processes. Encourage regionally-based intermodal gateway responses. Actively engage and support the establishment of international standards to facilitate freight movement. |

| Proactively identify and address emerging transportation needs. | Develop data and analytical capacity for making future investment decisions. Conduct freight-related research and development. Maintain dialogue between and among public and private sector freight stakeholders. Make public sector institutional arrangements more responsive. Make the public sector transportation system and investments more accountable and performance oriented. Establish the federal role in freight transportation. |

| Maximize the safety and security of the freight transportation system. | Pursue activities that improve safety of the freight transportation system. Manage public exposure to hazardous materials. Ensure a balanced approach to security and efficiency in all freight initiatives. Preserve redundant capacity for security and reliability. |

| Mitigate and better manage the environmental, health, energy, and community impacts of freight transportation. | Pursue pollution reduction technologies and operations. Pursue investments to mitigate environmental, health, and community transportation impacts. Promote adaptive reuse of brownfields and dredge material. Prevent introduction of or control invasive species. Pursue energy conservation strategies and alternative fuels in freight operations. |

The Framework for a National Freight Policy continues to evolve as a joint effort of USDOT and its partners in the public and private sectors to inventory existing and proposed strategies, tactics, and activities to improve freight transportation (USDOT 2008). The framework's focus is national rather than federal, and reflects the critical roles of the Federal Government, States, localities, and the private sector. Each strategy has at least one tactic, each tactic has at least one activity, and each activity has "owners" who are responsible for establishing milestones and articulating the consequences of moving the activity forward. The Framework is structured to identify examples of good practice, actions that would benefit from increased collaboration, conflicts that require resolution, and issues that need more attention. It provides a common ground for discussion rather than a forum for developing a formal industry consensus or official USDOT views.

Government Responses at the National Level

Freight is the focus of several congressional actions, including the most recent reauthorization of the Federal-aid Highway Program through the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) (P.L. 109-059). SAFETEA-LU authorized $4.6 billion for freight-oriented infrastructure investments (Table 4), expanded eligibility for financing freight projects under the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Program, extended the State Infrastructure Bank Program, and modified the U.S. tax code to encourage up to $15 billion in investment in freight facilities through private activity bonds.

| Projects of National/Regional Significance | $1.779 billion over 5 years |

| National Corridor Infrastructure Improvement | $1.948 billion over 5 years |

| Coordinated Border Infrastructure Program | $833 million over 5 years |

| Freight Intermodal Distribution Pilot Grant Program | $30 million over 5 years |

| Truck Parking | $25 million over 4 years |

| Total | $4.615 billion |

Beyond concrete and steel, SAFETEA-LU funds freight planning capacity building (P.L. 109-059, Section 5204), supports freight analysis through the surface transportation congestion relief solutions research initiative (P.L. 109-059, Section 5502), and established the National Cooperative Freight Research Program (NCFRP) (P.L. 109-059, Section 5209), and Hazardous Materials Cooperative Research Program (HMCRP) (P.L. 109-059, Section 7131). The research programs provide about $2 million per year on a range of projects (Table 6). Public agencies and private industry work closely together on the NCFRP and HMCRP and actively seek new participants from diverse academic backgrounds and experience to guide individual research through project panels.

| Project Number | Project Title |

|---|---|

| NCFRP 01 | Review and Analysis of Freight Transportation Markets and Relationships |

| NCFRP 02 | Impacts of Public Policy on the Freight Transportation System |

| NCFRP 03 | Performance Measures for Freight Transportation |

| NCFRP 04 | Identifying and Using Low-Cost and Quickly Implementable Ways to Address Freight-System Mobility Constraints |

| NCFRP 05 | Framework and Tools for Estimating Benefits of Specific Freight Network Investment Needs |

| NCFRP 06 | Freight-Demand Modeling to Support Public-Sector Decision Making |

| NCFRP 09 | Institutional Arrangements in the Freight Transportation System |

| NCFRP 10 | Separation of Vehicles: Commercial Motor Vehicle Only Lanes |

| NCFRP 11 | Current and Future Contributions to Freight Demand in North America |

| NCFRP 12 | Specifications for Freight Transportation Data Architecture |

| NCFRP 13 | Developing High Productivity Truck Corridors |

| NCFRP 14 | Truck Drayage Practices |

| NCFRP 15 | Understanding Urban Goods Movements |

| NCFRP 16 | Representing Freight in Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Models |

| NCFRP 17 | Synthesis of Short Sea Shipping in North America |

| HMCRP 01 | Hazardous Materials Commodity Flow Data and Analysis |

| HMCRP 02 | Hazardous Materials Transportation Incident Data for Root Cause Analysis |

| HMCRP 03 | A Guide for Assessing Emergency Response Needs and Capabilities for Hazardous Materials Releases |

| HMCRP 04 | Emerging Technologies Applicable to Hazardous Materials Transportation Safety and Security |

| HMCRP 05 | Evaluation of the Potential Benefits of Electronic Shipping Papers for Hazardous Materials Shipments |

| HMCRP 06 | Assessing Soil and Groundwater Environmental Hazards from Hazardous Materials Transportation Incidents |

SAFETEA-LU also established the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission (P.L. 109-059, Section 1909(b)), which stated, "The Commission believes the national interest in quality transportation is best served when ... freight movement is explicitly valued. Operation of private and public sector freight systems (including rail, trucking, waterways, and ports) that fully serve the needs of the Nation's economy is a priority" (NSTP-RSC 2008). The Commission identified freight as a key focus area in developing and funding a future transportation program (see box on page 32).

|

National Freight Transportation Program to Enhance U.S. Global Competitiveness The National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission supports the creation and funding of a national freight transportation program to implement much needed infrastructure improvements. The program will bring together local, state, and federal interests to make the national transportation system more reliable and efficient. As envisioned, the program will "provide public investment in crucial, high-cost transportation infrastructure," especially on networks that carry large volumes of freight, such as intermodal connectors, sections of interstate highways near port facilities, strategic national rail bridges, and corridor development. Public-private projects that have the potential to facilitate international trade, relieve congestion, or enable "green" intermodal facilities would be included under this program. A key activity of the National Freight Transportation Program is the development of a national strategic plan to set goals and guide activities. The U.S. Department of Transportation would use state and metropolitan-area plans as a basis for developing the national plan. USDOT would work with states, local governments, multistate coalitions, and other public and private-sector stakeholders to set state and metropolitan-area performance standards for their programs. Each state and metropolitan area would be expected to meet national standards. Only projects identified in the national plan would be eligible for federal funds. Federal participation in individual projects would be set at 80 percent, with higher participation levels based on the extent of national benefits. Apart from demonstrating that a proposed project under a plan is cost effective and justified, additional federal requirements would be kept to a minimum. From National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission, "Transportation for Tomorrow: Report of the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission," Volume 1, 2008, at: www.transportationfortomorrow.org/final_report. |

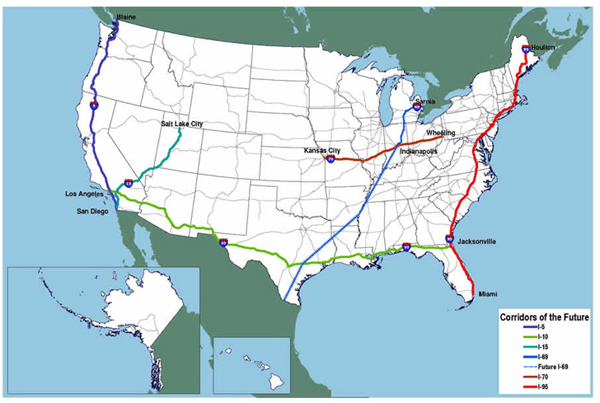

Since passage of SAFETEA-LU, USDOT has launched the Corridors of the Future program, a federal initiative aimed at reducing congestion and improving freight transportation efficiency through multijurisdictional planning and collaboration. Six corridors, identified in Figure 15, were selected from a pool of 38 to participate in the program. The six corridors account for nearly 23 percent of daily Interstate travel. USDOT and representatives from the six corridors focus on 1) alternatives to tax-revenue financing, 2) regional planning and project development, and 3) performance measures for the corridor. These issues are at the forefront of how the transportation network will be advanced in the coming decades.

Figure 15. Corridors of the Future

The Corridors of the Future program is part of the broader USDOT initiative "National Strategy to Reduce Congestion on America's Transportation Network." This initiative also includes urban partner-ships to reduce metropolitan congestion through pricing strategies and innovative technologies, as well as measures to enhance aviation system capacity. For more information, visit www.fightgridlocknow.gov.

Other federal freight initiatives include:

- The establishment of the cabinet-level Committee on the Marine Transportation System to coordinate the many federal agencies with responsibilities for the complex and diverse system of waterways, ports, and their intermodal connections. (For more information, visit www.cmts.gov.)

- The Motor Carrier Safety Assistance Program of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration to improve safety among motor carriers. (For more information, visit www.fmcsa.dot.gov/safety-security/safety-initiatives/mcsap/mcsap.htm.)

- The Hazardous Materials Emergency Preparedness grant program of the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration to provide financial and technical assistance as well as national direction and guidance to enhance state, territorial, tribal, and local hazardous materials emergency planning and training. (For more information, visit www.phmsa.dot.gov/hazmat.)

- The analysis and professional development programs of FHWA's Office of Freight Management and Operations to provide 1) a comprehensive picture of commodity movements through its Freight Analysis Framework; 2) highway travel time and reliability measures through its Performance Measurement Program; 3) new forecasting methods through its Freight Model Improvement Program, and 4) training, technical assistance, and information sharing among professionals in public agencies and industry through its Freight Professional Development Program. (For more information, visit www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight).

- The Smartway program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to provide the trucking industry with technical assistance and incentives to reduce long-haul truck energy consumption and emissions. (For more information, visit www.epa.gov/smartway.)

Responses at the State Level

Many state departments of transportation have established freight offices or designated freight coordinators, and several have initiated statewide freight plans. For example, the Minnesota Department of Transportation created a Freight Planning and Development Unit to 1) review the Department's role in freight transportation; 2) develop strategies for improving freight information; and 3) integrate freight transportation into the policy, planning, and investment processes. (For more information, visit www.dot.state.mn.us/ofrw/freight.html.)

Washington State's efforts go beyond planning to include financing freight projects though its Freight Mobility Strategic Investment Board. The Board's mission is to develop a comprehensive and coordinated state program to facilitate freight movement and to mitigate its effects on local communities. To date, the Board has funded dozens of freight mobility projects and provided technical assistance to eliminate chokepoints so that freight moves smoothly and communities experience fewer disruptions in local traffic. Board-funded projects must be ready for construction within 12 months of receiving funding. To meet this requirement, the Board works with project staff to leverage funding, develop partnerships, and build negotiation skills. (For more information, visit www.fmsib.wa.gov.)

Many states realize that solutions to their freight problems require actions well beyond the state's borders. As a result, 12 corridor coalitions have been created to pursue those solutions. (For more information, visit www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/corridor_coal.htm.) Some coalitions sponsor research to better understand freight problems throughout their corridor, while others develop specific plans through the Corridors of the Future program. One group, the I-95 Corridor Coalition, is developing a Freight Academy to provide continued education to the region's freight transportation professionals. (For more information, visit www.freightacademy.org.)

Growing state interest in freight issues is underscored by activities of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), including publication of the Freight Bottom Line Report, formal adoption of several freight policy proposals, and the ongoing work of five freight committees and subcommittees. (For more information, visit http://freight.transportation.org.) AASHTO and FHWA cosponsor biennial Freight Transportation Partnership meetings attended by federal and state officials and private sector representatives. Participants share experiences and discuss organizational and institutional issues that need to be addressed to better advance freight transportation projects more effectively. (For more information, visit www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/partnership.htm.)

Responses at the Local Level

MPOs in larger cities are developing freight plans and programs and engaging private-sector stakeholders through advisory committees. For example, the Atlanta Regional Commission and Georgia DOT together developed a data-driven, policy-based Regional Freight Mobility Plan for the Atlanta metropolitan area. The Plan examined regional goods movement by all modes and culminated in the development of a framework to address regional freight mobility needs and challenges. (For more information, visit www.atlantaregional.com/freightmobility.) Similar efforts are underway in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

Another notable local initiative is the PierPASS OffPeak program, which was created by the marine terminal operators at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to alleviate truck traffic congestion and improve air quality in the region. (For more information, visit www.pierpass.org.) Trucks with loaded containers entering or exiting marine terminals during peak hours are charged a terminal mitigation fee. The fee encourages cargo owners and their carriers to move cargo at night and on weekends and defrays the additional costs of keeping the terminal open longer hours. As a result, congestion is reduced during peak daytime periods at port gates and on major highways around the ports, and air quality is improved.

Private Sector and Public-Private Responses

Carriers, shippers, terminal operators, and other private sector players in the freight transportation industry deal with the freight challenge on a daily basis, either through the actions of individual businesses, collective action through associations, or cooperative ventures with public agencies. For example:

- Walmart established a Sustainable Value Networks program with its suppliers and other partners to reduce logistics costs through operating efficiency improvements, less wasteful packaging, and alternative fuels use. (For more information, visit www.walmartstores.com/Sustainability/7672.aspx.)

- The Ocean Carrier Equipment Management Association, an association of 18 major ocean common carriers, formed the Consolidated Chassis Management LLC in 2005 to develop and own chassis pools. It currently has more than 35,000 chassis under management at pools in Denver, Salt Lake City, Tampa, Memphis, Nashville, Charleston, Atlanta, Charlotte, Jacksonville, and Savannah. (For more information, visit www.ocema.org.)

- Several associations are proposing new or additional infrastructure investments in freight corridors, such as the "Critical Commerce Corridors" program of the American Road and Transportation Builders Association and the "Let's Rebuild America" program of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

- The Intermodal Freight Technology Working Group (IFTWG), a public-private partnership, focuses on the identification and evaluation of technology- based options for improving the efficiency, safety, and security of intermodal freight movement. (For more information, visit www.intermodal.org/iftwg_files/index.shtml.) The IFTWG worked with FHWA to establish the Universal Electronic Freight Manifest initiative, which provides all supply chain partners with timely access to shipment information. (For more information, visit www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/intermodal/efmi/index.htm.)

![]() You will need the Adobe Acrobat Reader to view the PDFs on this page.

You will need the Adobe Acrobat Reader to view the PDFs on this page.

To view Excel files, you can use the Microsoft Excel Viewer.