Strategies to Enhance North American Freight Productivity and Security

The preceding sections suggest a compelling public policy challenge in meeting the Nation's needs for enhanced freight productivity and security, as agencies at all levels of government are called upon to address and balance numerous and often seemingly conflicting public policy goals. As has been noted, freight and trade transport have been fundamental to the growth and development of the United States. The necessity of freight movement has created a landscape of major urbanized areas, connected to farming and manufacturing regions and to each other by multimodal transportation corridors. This domestic linkage has been extended by the dramatic growth in international trade with Canada and Mexico, our NAFTA partners. The result is an extensive, reliable, and highly redundant network of highways, railroads, inland waterways, coastal ports, and air-freight hubs, connecting all of North America and sustaining economic growth and trade.

To meet this public policy challenge, several strategies have been developed and are now being discussed widely among freight stakeholders. As defined by FAF and confirmed by discussions with multiple freight interests, the strategies are organized around the geography of freight and include international gateways, state and local transportation programs, and multijurisdictional corridors and regions. Within these geographic areas, two types of strategies are specified: 1) the creation of an institutional environment that supports the identification and advancement of freight concerns within the transportation development process and 2) the establishment of comprehensive and sustainable funding sources to support the implementation of selected freight-related programs and projects.

The strategies discussed here are elements of a comprehensive national freight mobility and productivity program, not specific legislative initiatives. Over the course of the next year, debate and discussion will continue as legislative development is advanced for the reauthorization of the federal surface transportation program and other modal legislative initiatives affecting air and marine interests. Information on the nature of impending freight mobility and productivity problems facing the nation, the geography and scope of the problems, and reasonable options to pursue to achieve the desired outcomes will add value and enrich the discussions that lay ahead.

International Freight Gateways

The growth in international trade expected through 2020 will place a continuing burden on international gateways and gateway communities. Gateways create a "free rider" transportation problem. The costs and congestion associated with trade are borne locally, while the benefits are distributed broadly throughout the county. In addition, as population continues gravitating to coastal and border regions, particularly the southern border, through demographic shifts and immigration, public agencies, port authorities, and the private sector will be faced with stiff competition for land and access by which improvements in freight efficiency might be advanced. Concerns about national security within the freight transport system will also focus on gateways, as the United States seeks to protect itself and its NAFTA trade partners against terrorism through the international trade system. These concerns suggest that the major objectives of any initiative to enhance international gateways should be to: 1) improve gateway throughput; 2) ensure national security; and 3) mitigate congestion and community impacts. Gateway projects are likely to combine existing or modified federal-aid programs and public/private partnerships through an innovative finance program underpinned by user fees, as was done with the recently opened Alameda Corridor.

The Alameda Corridor, the predecessor and model for TIFIA, brought together several funding sources from federal, state, and port programs, along with a user fee applied to shipments either using, or capable of using the corridor. The Corridor relies substantially on grade separations to promote safety and to improve the operational characteristics of rail, to minimize truck drayage and traffic conflicts in and around the ports, and to minimize the community impacts of freight improvements. In addition, during construction the Corridor established a broad employment development program for surrounding neighborhoods, with significant minority and disadvantaged populations, to provide long-term economic opportunities within communities affected by transport systems. The Corridor is a model for public/private cooperation in addressing multiple social, economic, and environmental goals. It clearly illustrates how a systemic approach of multimodal development, involving multiple jurisdictions and combined funding sources, can be brought together to address a problem of regional and national interest.

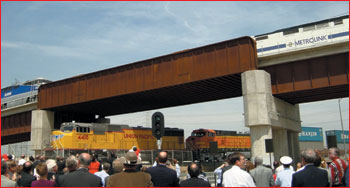

The Redondo Junction project separates passenger rail from

freight rail by elevating Amtrak and Metrolink railroad lines over

the Alameda Corridor in Los Angeles. Source: Alameda Corridor Transportation

Authority

Port gateway projects under development include the I-710 freeway serving the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles and the Portway and Port Inland Distribution Network serving the Port of New York and New Jersey. These gateway projects generally exceed $500 million, and some go much higher. Other surface transportation projects are being considered to improve NAFTA land gateways, such as the Michigan/Ontario frontier, and to facilitate rail movements in Chicago that serve national and international trade. In concert with an international gateways initiative, stakeholders have suggested that a National Freight Advisory Council could be established in reauthorization to provide private sector advice to USDOT on international gateway and other investments to enhance national freight productivity.

State and Local Transportation Programs

The 3-C (continuing, cooperative, comprehensive) transportation planning process was established by federal law in the 1960s to support statewide and metropolitan planning. Although freight movement is implicit in transportation planning, it has only been explicitly called for since the 1990s. Both ISTEA and TEA-21 defined freight as an element that must be considered and included in each of these planning processes. As noted earlier, many states have initiated efforts to incorporate freight in both state and metropolitan planning, partly in response to these two federal legislative initiatives. These efforts have been significant and useful in many states and localities, but they have not been adopted completely throughout the Nation. As a result, the consideration of freight and trade transport issues has been inconsistent, with strong consideration in some areas, far less in others. Several regional coalitions have also emerged, focusing primarily on development of specific corridors. Others have formed to address regional freight issues, as well. Most recently, in response to growing trade with Canada and Mexico, and reinforced by the terrorist attacks of September 11, with their implications for international trade security, freight planning has been advanced through creation of binational planning arrangements, including involvement of U.S. Customs and the other Federal Inspection Services with responsibility for international trade transport.

To improve state and metropolitan consideration of freight, and to secure continued private interest and involvement in planning, new institutional means are needed to simplify the involvement process and to shorten the time expectation for delivery of measurable system improvements. A "one stop shopping" model for freight involvement has been established in some states, and other states are experimenting with similar models to engage freight interests more effectively. These models address the three major objectives of strengthened public/private cooperation in freight: (1) improve reliability of freight movement; (2) support state and local economic development; and (3) coordinate freight transportation investment, economic development, and trade initiatives. These models do not replace or replicate existing state and local planning functions. Rather, they provide a single point of contact for freight interests, simplifying the involvement process for the private sector, while providing a point of accountability and access to public programs. State DOTs and MPOs are faced with a large and complex set of issues to be addressed; freight is often viewed as simply one issue among many. Identifying a collaborative mechanism or suitable point of contact for freight issues could substantially improve the consideration of freight within statewide and metropolitan programs. Governor-directed efforts in Florida and Washington State have enabled these states to focus additional attention to freight and trade transport issues without constraining other interests, and provide the executive level authority and guidance needed to help local freight advisory groups to function more effectively.

Process improvements within state and local transportation programs should enable a more effective focus on freight investment needs within these geographic areas, particularly with regards to intermodal development. Traditionally, transportation systems have been developed modally and independently, with highway planning conducted within the public arena, and rail and port planning conducted either fully within the private sector, or as a shared responsibility. The result has been an orientation to modal specific networks, without full regard for intermodal connections and development opportunities. In response to this, TEA-21 required USDOT to analyze and report on the adequacy and needs of NHS freight connectors. The NHS Freight Connectors report, submitted to Congress in December 2000, documented the condition and issues associated with NHS intermodal freight connectors, often referred to as "the last mile."

While these relatively short highway sections represent less than 1 percent of NHS mileage, they are the critical connections to enhance intermodal opportunities for shippers and improved asset management of the nation's freight infrastructure system. Additional attention must be given to these vital sections, especially within congested metropolitan areas, to help realize the full potential of the Nation's intermodal system. Almost 50 percent of these NHS sections are partially or entirely owned by local governments, as opposed to the remainder of the NHS, which is almost entirely owned and operated by States. Connectors often do not get the priority at local levels because of funding constraints or other priorities.

ISTEA and TEA-21 each emphasized simplification and flexibility over the creation of categorical programs. In keeping with these principles, connector solutions are likely to concentrate on a call for increased state and local focus in the planning process, innovative financing, and greater cooperation with private sector freight interests. These approaches will ensure that an appropriate level of condition and serviceability is defined for critical connectors, with federal-aid eligibility assured to enable necessary funding for connector improvements. These approaches would also allow maximum state and local flexibility, while ensuring a public sector response appropriate to the specific needs of the freight community.

Multistate Trade Areas and Corridors

The Freight Analysis Framework, viewing freight movement from a national and continental perspective, graphically illustrates the importance of long-distance trade corridors and regional trade transport networks to the efficient and effective flow of commerce. State and local agencies may consider freight movement external to their borders in their planning processes, but programs are generally developed in accordance with the needs and priorities of the state or local government in question, not its surrounding jurisdictions. An ISTEA-required study on the adequacy of North American borders and corridors to accommodate trade helped generate national interest in multijurisdictional approaches to regional and corridor transport development. Corridor coalitions—spurred by the potential development of a multistate corridor, binational coalitions emphasizing cross border trade efficiency, and regional coalitions focusing on identification of regionally significant multimodal subnetworks—have formed and continue to form to raise the awareness and interest in multijurisdictional approaches to transportation issues. Institutionally, groups are using pooled funding mechanisms and congressional assistance to support multijurisdictional planning efforts. The challenge has been twofold: (1) the institutionalization of these efforts, with appropriate links to the authorized state and local planning processes and (2) the identification of funding for the implementation of agreed upon activities and projects, without jeopardizing other state and local transportation priorities.

Trucks queue up to enter a maritime port terminal in southern

California.

Source: Tom Pavia

TEA-21 includes a Borders and Corridors program to support multijurisdictional planning, including regional, corridor, and binational approaches. The program is discretionary, with project solicitations reviewed for innovation and breadth of support. This program, while heavily oversubscribed, has been considered a catalyst for multijurisdictional approaches toward corridor, border, and regional trade transport development. The program, originally envisioned to support coordinated planning, environmental assessment, and other preconstruction activities, is being used increasingly as an additional funding source for conventional construction activities. This expansion in eligibility has constrained its use in advancing multijurisdictional institutional approaches to transport development, and in emphasizing the need for border initiatives to improve the efficiency, safety, and national security of border crossings. States and MPOs are currently able to build coalitions and engage in coordinated multijurisdictional planning, but implementation issues are often a challenge. Although agreement on general principles is relatively easily obtained, agreement on multiyear program strategies and sequencing of investments across jurisdictions has proven difficult. Borders and Corridors Programs have become models for encouraging multistate and multijurisdictional approaches. A strengthening of objectives and a directive for coordinated implementation strategies, in addition to planning, could enable jurisdictions to accommodate corridor and regionwide freight concerns more effectively. New institutional arrangements such as interstate compacts have been suggested to more effectively manage multistate corridor and regional projects.

In addition to institutional innovations in support of multijurisdictional approaches, financing also is a major concern. Coalitions, such as the Latin American Trade Transportation Study, a multistate coalition sponsored by the Southeastern Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials; the I-95 Corridor Coalition; and the International Mobility and Trade Corridor, a binational initiative between Washington State and British Columbia, have each addressed issues of funding across state lines, across modal interests, and across international boundaries. The funding problems identified suggest programmatic and legislative improvements that can remove some of the barriers and facilitate the leveraging of public and private capital investment to make the necessary freight improvements while maintaining the integrity of the broader transport network. Innovative finance solutions need to be further explored. Multistate mechanisms for TIFIA, State Infrastructure Banks, and enhanced bonding mechanisms need to be considered.

National Initiatives for Freight Productivity and Security

Initiatives that address institutional and funding concerns in gateways, regions and corridors, and support state and metropolitan transportation planning, will enhance the ability of these geographic areas to meet the challenges of improving freight productivity. However, broader objectives such as ensuring security and improving overall freight system performance call for other, more nationally oriented strategies. The application of freight technologies to support freight transport security efforts and strengthen the integrity of global supply chains will require leadership in testing and deploying new technologies and information systems and agreement on international standards and protocols. Information sharing among government agencies and industries, through mechanisms such as the U.S. DOT/U.S. Customs Container Security Working Group, must also be continued and strengthened. Furthermore, it is imperative that the United States and its trading partners continue to work together to accelerate the adoption of international data and technology standards. The adoption of standards will allow global interoperability of security sensors, for example, and help reduce information islands that now exist throughout the freight transportation network. The World Customs Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and other global entities can facilitate these efforts.

To improve national freight capabilities, emphasis should also be given to developing freight data/tools and building professional capacity. A comprehensive data and analytical system, building on the success of the Freight Analysis Framework, will enable decisionmakers to better understand trends, make informed investment decisions, and support safe and reliable transportation operations. Such a comprehensive program should be multimodal in nature, including more comprehensive commodity flow data and the development of tools for assessing regional, corridor, and local networks, forecasting freight demand, and evaluating freight investments. Specifically, new models need to be developed to measure the effects of growing volumes of freight on congestion and the environment and evaluate the effects of economic growth on freight demand. Historically, transportation demand forecasting models have tended to focus on passenger travel.

Likewise, national programs are needed to develop freight-specific educational and training opportunities to close a serious gap in knowledge of freight transportation's unique characteristics and needs. Professional capacity building programs will require both immediate and long-term efforts focusing on such topics as emerging freight trends, data needs, benefits/costs of investments, forecasting growth, and planning and financing improvements. These programs will provide much needed information to states, MPOs, and the private sector in planning for future growth in freight transportation.

previous | next