Fundamentals: How to Manage and Operate Transportation Systems to Support Livability and Sustainability

This section highlights nine key elements — “fundamentals” — for managing and operating transportation systems in ways that support livability and sustainability. Many of the activities described in the fundamentals are already part of transportation agency best practices, but may not be applied as part of a more comprehensive, balanced approach to advancing sustainability and livability in transportation operations. M&O strategies are rarely applied in isolation, and approaches from across the fundamentals should be combined to maximize the benefits to communities.

The fundamentals are:

- Operate to serve community priorities.

- Increase opportunities for safe, comfortable walking and bicycling.

- Improve the transit experience.

- Support reliable, efficient movement of people and goods.

- Manage travel demand.

- Provide information to support choices.

- Support placemaking.

- Use balanced performance measures.

- Collaborate and coordinate broadly.

Each of these fundamentals is described below, along with specific examples of their application in different communities across the U.S. and internationally. The individual M&O strategies identified in these sections are examples of good practices but are not fully comprehensive or ranked in any priority order.

Operate to Serve Community Priorities

The choice and implementation of M&O strategies should respond to community priorities, reflecting the community’s goals and objectives for the transportation system and its larger context as expressed through the planning process. These goals provide the basis for judging what is considered successful operation of the transportation system. By focusing on community priorities, transportation system operations can help a community achieve its broader goals.

Methods for Incorporating Community Priorities into Operations

|

Context is an essential consideration in determining how

to operate the system. How a roadway operates should depend

in part on its character—for instance, a major urban

arterial, a small-town main street, a neighborhood street,

and a scenic rural road will each have different characteristics,

operating speeds, and levels of emphasis on elements such

as integration of different modes.

This approach runs in parallel to the idea of context-sensitive design, which calls for transportation facility design to consider how the facility will fit within its total context (physical, aesthetic, historic, etc.). As with that approach, there must be a certain amount of flexibility in the application of traditional roadway operating standards and recognition that systems can still be operated safely while responding to broader community goals.

For example, the Capital District Transportation Committee

(CDTC) in the Albany, New York region has established congestion

management principles as part of both its metropolitan transportation

plan and its congestion management process (CMP). CDTC believes

that what the residents of the region want—as articulated

in the regional vision and as expressed though resident

involvement in corridor and project-level studies—must

help define how congestion management is applied in the

region. A key element of this is the region’s decision

to implement demand management strategies and operational

strategies before capacity expansion when addressing regional

congestion. The M&O focus is

also influenced by public opinion polling CDTC completed

using surveys and public involvement. CDTC found that the

public wants more bicycle, pedestrian, and other improvements

and that travel time reliability (which can often be addressed

through M&O strategies) is the most important congestion

issue for travelers in the region.

Roadway operations need to be considered from multiple

perspectives: the function a street provides within the

overall transportation system, its users, and the communities

through which it passes. The City of Pasadena, California,

is developing a context-based street classification system

to allow planners and operators to more easily identify

the appropriate roadway treatments for the context and function

of the roadway. This system builds on a long-standing

program of residential neighborhood traffic calming through

the city’s Neighborhood Traffic Management Program.

The program relies on outreach into neighborhoods to identify

local concerns and to develop consensus on solutions. In

recognition that improvements in one neighborhood can push

traffic from one neighborhood to another, the program is

now being expanded to take a multi-neighborhood approach

to traffic management to improve the interfaces between

local residential streets and major streets.

Neighborhood Greenways ProgramPortland, Oregon To meet the city’s goals for increasing bicycle mode share, the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) has developed a network of “neighborhood greenways” (or “bicycle boulevards”). Neighborhood greenways use existing low-traffic, local roads to create high-quality bicycle and pedestrian facilities linking residential areas to schools, parks, and businesses. This program has used relatively low-cost M&O strategies to transform existing streets into a network of multimodal facilities that promote active transportation and neighborhood livability. Studies to date show that the greenways are well-received by neighborhoods, increase bicycling and walking, and divert minimal amounts of through traffic to nearby local streets. For more information: http://www.portlandonline.com/transportation/index.cfm?c=50518. Photo source: G. Raisman, PBOT |

Sample Contexts and Priorities

Rural Areas

- For travel between towns, priorities may focus on safe and consistent roadway operations for personal automobiles and trucks, as these modes are often the key to mobility in this context. The focus also may be on balancing roadway safety and efficient freight movement with environmental protection and preserving scenic vistas to attract tourism.

- Within small towns, priorities may be more focused on balancing the needs of through and local traffic, using such strategies as access management, traffic signal coordination, and roundabouts to move vehicles through efficiently while still allowing safe and convenient pedestrian movement and preserving local character. Communities may also be concerned with providing more transportation options to local residents through demand-response transit and intercity bus services.

Pedestrian Safety ProgramMiami-Dade County, Florida Miami-Dade County has one of the highest rates of pedestrian fatalities per population for large metropolitan regions. To combat this, the county recently implemented a comprehensive pedestrian safety improvement program on eight high-crash corridors. The program focused on immediate implementation of low- and medium-cost treatments, including several M&O strategies; as a result, the total cost of the program was less than $1.1 million. Before-and-after crash data along the target corridors show that pedestrian crashes decreased by over 40 percent after implementation. Source: University of Florida, Miami-Dade Pedestrian Safety Project: Phase II Final Implementation Report and Executive Summary, August 2008. |

Urban and Suburban Areas

- In urban centers, priorities will typically incorporate a broader range of modes, often with more focus on supporting transit, pedestrians, and bicycles and facilitating shared modal options like car sharing and bicycle sharing.

- On major arterials and in activity centers, person movement rather than vehicle movement may be the focus, with strategies like TSP and parking management playing key roles.

- Residential neighborhoods and town centers may have a different modal hierarchy, giving precedence to pedestrians and bicyclists over automobiles. The operational priority may be to discourage through traffic to help preserve quiet, safe streets in residential neighborhoods or to encourage more foot traffic in town centers to support local businesses.

- On freeways, particularly where capacity expansions are cost- or space-prohibitive, the focus may be on encouraging higher vehicle occupancies that allow congested roadways to carry more people during peak periods. This can be achieved by linking more typical roadway management strategies with demand management and managed lanes. Managed lanes are a set of lanes where operational strategies are proactively implemented and managed in response to changing conditions, including through the use of roadway pricing (e.g., high-occupancy toll lanes) and/or restricting which vehicles can enter the lanes (e.g., high-occupancy vehicle, express, or truck-only lanes).

Increase Opportunities for Safe, Comfortable Walking and Bicycling

Walking and bicycling are central to sustainability and livability. These modes are low cost and broadly available. These modes provide many environmental benefits: they are non-polluting modes, their infrastructure requirements are less intense than other modes, and they can often be supported through existing infrastructure. Walking and bicycling also provide a variety of community benefits: they contribute to the health of individuals, encourage social interaction that strengthens communities, and support the vitality of retail districts and neighborhoods.

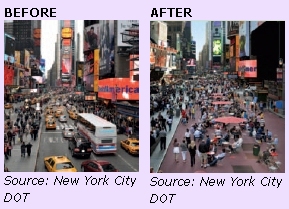

Green Light for Midtown and New Pedestrian Spaces in New York City

Increasing opportunities for walking and bicycling can also involve recognizing situations there these modes are, or should be, the dominant mode. This can be done to attract more pedestrians and bicyclists or address issues with already high volumes of these modes. A high-profile example of this is the 2009 creation of pedestrian areas in Times Square and Herald Square in New York City that was completed under the Green Light for Midtown project. The project was intended to improve safety, mobility, and livability along the Broadway corridor, which bisects the famous Times Square. The corridor suffered from inadequate pedestrian facilities that often led to people walking in the streets, long crossings and multi-legged intersections, and confusing traffic patterns. To address this, New York City DOT removed vehicular traffic from Broadway in Times Square and Herald Square, in coordination with other traffic changes to signal timing, roadway geometry, crosswalk shortenings, and parking regulation changes. Within the new pedestrian spaces, a variety of streetscape improvements were implemented. Evaluations of the project found that one year later:

Source: New York City DOT, Green Light for Midtown Evaluation Report, January 2010. |

While the basic infrastructure to support walking and bicycling—such as sidewalks, bicycle lanes, and shared-use paths—are important, the attractiveness and function of these modes is heavily affected by the management and operation of the transportation system. For example, traffic signal timing determines the amount of time pedestrians have to cross streets and how long they have to wait before crossings. Pedestrian countdown walk signals reduce confusion and help pedestrians make better crossing choices by informing pedestrians of the number of seconds remaining to safely cross the street. Along with infrastructure improvements such as wider sidewalks, pedestrian refuges in medians, and well-designed turning slip lanes (a turn lane offset at an intersection with a pedestrian refuge), pedestrian countdown signals can help make walking safer and more attractive. Similarly, incorporating bicycle detector loops at actuated signals ensures that bicycles will be able to safely cross intersections without undue wait, particularly in the off-peak periods.

| Tubular channelizers Rectangular rapid flash |

Some key M&O-related strategies to promote walking and bicycling are:

- Traffic Calming—A combination

of M&O and physical measures to encourage lower speeds

and reduce traffic volumes, which improve pedestrian and

bicyclist safety. Speed limit reductions

combined with improved crosswalks, bicycle lanes or shared-lane bicycle markings, on-street parking management, signage, and enforcement can help create visual cues that define areas that demand

lower speeds and additional awareness of nonmotorist roadway users.

The Iowa DOT tested various low-cost traffic calming treatments in rural communities to help slow traffic on major roads as they entered the communities. Strategies that showed the greatest effect on traffic speeds were speed feedback signs (signs that measured and displayed the actual approach speeds), colored pavement, on-pavement speed signing, and creation of center medians with tubular channelizers (poles).18 - ITS Technologies—At signalized

intersections, traffic signal timing and pedestrian countdown

signals can have an important effect on enabling people

to walk or bicycle across streets safely. At nonsignalized

intersections, rectangular rapid flash beacons attached

to pedestrian signs can alert motorists to the presence

of a pedestrian crossing or preparing to cross. When the

pedestrian activates

the system, either by using a push-button or through detection from a sensor, the lights begin to flash, warning the motorist that a pedestrian is in the vicinity of the crosswalk. - Complete Streets—Complete streets are designed and operated to enable safe access and mobility for transportation system users of all ages and abilities, including pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists, and public transportation users. M&O strategies play an important role in helping communities implement complete streets policies once they are adopted and can provide additional options where infrastructure changes are not feasible due to physical or financial constraints. M&O strategies such as traffic signal timing progression that are optimized for transit or bicycle speeds rather than motor vehicle speeds can help to improve multimodal efficiency on complete streets and distinguish them from surrounding auto-oriented streets.

- Safe Routes to Schools—Safe Routes to School programs, implemented by school districts and local governments, encourage children to walk and bicycle to school through a combination of education, outreach, and infrastructure improvements. M&O strategies can be used effectively to delineate school zones, alert motorists to the presence of children, and create an environment that promotes multimodal safety and accessibility. Strategies include retroreflective school crossing signs, changeable message signs and speed feedback signs, school zone pavement markings, crossing guards and student patrols, accessible pedestrian signals, and high-visibility crosswalks. FHWA provides funding and resources for Safe Routes to School; some State and local governments provide additional support and funding.

- Bicycle Sharing—These programs provide public bicycles at docking stations at various locations throughout an urban area, available on demand to users. Users can pick up a bicycle at a station near their origin and return it at any station in the system. Smartcards or payment kiosks are used to gain access to the bicycles. Several bicycle sharing programs have launched in the United States over the last few years, with one of the most successful in Washington, DC, and neighboring Arlington, Virginia. After a pilot program to demonstrate the model’s feasibility, Capital Bikeshare was launched in September 2010 and as of April 2011 had over 110 stations, 1,100 bicycles, 10,700 members, and had logged over 300,000 rides. Several other major U.S. cities have launched bicycle sharing programs, including Chicago, Boston, Minneapolis, Denver, Des Moines, Miami, and San Antonio.

San Antonio B-Cycle San Antonio B-Cycle was recently initiated with 140 bicycles at 14 locations located throughout the downtown areas. Individuals can purchase a 24-hour, 7-day, or annual membership. The program was implemented to improve travel choices, save travel costs, reduce motor vehicle travel, and support healthy living as part of implementation of the city’s Strategic Transportation Plan and Climate Action Plan. From the program’s initiation on March 28, 2011, through May 10, 2011, there were 4,357 bicycle trips through the program. For more information: http://sanantonio.bcycle.com. |

Improve the Transit Experience

Improving travel choices by increasing the attractiveness and performance of public transit is a central component of making communities more livable and sustainable, especially in more compact cities and towns where transit can operate cost-effectively. The benefits of transit for communities are numerous. Transit helps reduce vehicle travel and congestion, leading to fewer criteria pollutant and GHG emissions. For individuals, using transit instead of an automobile saves fuel and parking costs and reduces wear and tear on vehicles. When riders can reduce car ownership as a result of transit and other transportation options, household savings can be substantial. Using public transit instead of driving can reduce stress for travelers, improving their overall quality of life. For a community, transit boosts social equity by providing mobility and accessibility to individuals who are unable to drive or have limited access to a vehicle. At a larger scale, by mitigating congestion and increasing vehicle occupancies, transit can help communities avoid costly roadway expansions.

M&O strategies can improve the transit-riding experience and help make transit more competitive with private automobiles. Within the context of M&O, bus transit is often a key focus because it operates in mixed traffic or shared rights of way.

M&O strategies for transit can be broken into several categories.

Roadway operations, which enable transit vehicles to operate more efficiently and reliably within and around general traffic. Strategies include:

- Transit signal priority (TSP): Signals can be programmed so that as a bus approaches an intersection, it gets a green light sooner or the light stays green a little longer to reduce the time spent waiting at intersections. TSP can improve on-time performance and decrease overall run time for a route without noticeably disrupting signal operations for general traffic. TSP can be tied to bus schedules so that priority is granted only to buses running behind.

- Queue jumps: Queue jumps are right-turn lanes or separate bus-only lanes at intersections that are given a green light before other lanes to allow the bus to get through the intersection before general traffic.

- Buses on shoulders: On highways, this strategy permits buses to used paved shoulders as a lane when traffic is slow. This strategy has been in use for nearly two decades in the Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota metropolitan area and a study of routes using the shoulders found ridership on those routes increased by 9.2 percent, even as overall system ridership decreased 6.5 percent.19

Metro Rapid Limited-Stop Bus SystemLos Angeles, California Los Angeles Metro has a system of rapid bus lines

with limited BRT features that improve service compared

to regular buses. Metro uses operational strategies

to both improve bus travel times (by reducing delay)

and make the service more appealing to new riders.

These strategies include:

Results:

For more information: http://www.metro.net/projects/rapid/. |

Transit system operations, which concern transit vehicle operations directly and how they interface with transit users. Strategies in this area focus on streamlining operations to make transit operate more seamlessly for passengers and the system operator. Some widespread techniques for doing this include automatic vehicle location (AVL) systems and related software that track the location of vehicles and help dispatchers and drivers maintain route and schedule adherence. Other strategies include:

- Improved payment methods: Faster payment methods speed vehicle boarding and can help buses improve on-time performance, along with simplifying fare collection. These methods include off-board fare collection, which collects fares at the station before passenger boarding, and proof-of-payment systems, which require passengers to have a valid ticket or pass that is subject to random inspection. Many systems now use smart cards, which can have a value loaded in person or via the Internet, and some international transit systems now also have pay-by-phone options. Smart cards in particular offer the opportunity of being able to work with multiple transit providers, simplifying transfers for transit users and expanding their access to more systems. The cards can also be linked to other transit modes, such as car sharing. To address both the cost and delays associated with fare collection, some smaller systems have opted to make their service free, thus alleviating delays during boarding while greatly improving the attractiveness of their services.

- Improved transit schedule coordination: Improved schedule coordination can help improve transfers between different transit services, reducing travel times and making transit a more attractive mode choice. Smooth, timely transfers are particularly important because out-of-vehicle wait times are documented to be perceived as much more onerous than in-vehicle travel times.20 Approaches to coordination include operating routes with the same headways so they align at certain transfer points, bringing all routes in to dwell at transit hubs for 3-5 minutes before they all depart, or tying feeder bus departures to the arrival of a main bus line or train. Schedule coordination works best where there is good on-time performance of routes.

- Circulator services: These specialized transit services generally link popular destinations within downtowns, university campuses, and similar areas. Circulator routes and schedules are meant to be easy to use for new riders, often using loop routes and headway-based schedules that do not require riders to consult a timetable. Many downtown circulators do not have fares or charge only minimal amounts and accept multiple fare media. Circulator vehicles are generally distinctive, branded separately from other local transit service, and are often provided through collaboration among the local transit agency, the local government, and local businesses or business groups.21

- Real-time information: By providing accurate, real-time information about the expected arrival of buses and trains, transit systems can help riders know when to leave for a station or bus stop, reducing actual wait time, and minimize uncertainty about arrivals, reducing perceived wait times. Information can be provided via displays in stations, the Internet (accessible to smartphone users as well), and text message systems (for all mobile phones).

- Access to and from transit stations: Multimodal access to and from transit stations can be supported through pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, which in turn may help alleviate the need to add more parking at major stations. Innovative transportation options are also helping to bridge the gap between transit services and riders’ origins and destinations, such as bicycle sharing, car sharing, real-time carpooling, and shared fleets of smaller neighborhood vehicles.

System-Wide Transit Signal PrioritySt. Cloud Metropolitan Transit Commission, St. Cloud, Minnesota The St. Cloud Metropolitan Transit Commission serves a small metropolitan area in central Minnesota. Following a successful pilot program, the entire traffic signal system in the area served by the agency was equipped with TSP equipment in 2003. A 2005 evaluation of the found:

With buses better able to stay on schedule, riders can make connections more easily and drivers can give passengers more time to board at stops, which increases customer satisfaction with the system. Source: St. Cloud Metropolitan Transit Commission, Transit Signal Priority (TSP) Deployment Project Final Report, 2005. |

M&O strategies should be prioritized for high-frequency, high-capacity transit, which in many communities may be BRT. BRT commonly consists of a range of M&O strategies, with specialized vehicles running on roadways or in dedicated lanes to provide faster, more reliable, and more comfortable service more typical of light rail transit. When BRT vehicles are running in existing roadway lanes mixed with cars, trucks, and local buses, coordinated M&O strategies are especially important. When coordinated with an integrated traffic signal management system and real-time route information, such as Los Angeles’ Metro Rapid BRT routes (see box on page 17), buses can deliver faster, more reliable service without affecting other vehicular traffic.

Support Reliable, Efficient Movement of People and Goods

One of the fundamental aims of M&O strategies is to actively support efficient and reliable mobility for people and goods. Being stuck in traffic, particularly in unexpected delays, wastes time and fuel, increases air pollution, creates stress and frustration for drivers, and undermines the timeliness of freight pickups and deliveries. Particularly in congested regions and corridors, M&O strategies applied strategically can help to avoid the need for major capacity expansions that are costly and may not fit within community visions while improving mobility for people and goods and supporting improved safety, air quality, regional economic vitality, and land use efficiency.

To support livability and sustainability, it is important that M&O strategies fit within the context of community goals and focus on the full range of system users. This means emphasizing efficient movement of people and goods rather than just vehicles and giving greater emphasis to modes or techniques that accommodate safe movement for the least cost in terms of economic, environmental, and social costs and the value of different trip purposes. For example, allowing transit buses to operate on the shoulders of roads during peak periods can help maximize the throughput of people on a facility. Inter-regional and interstate freight and recreational movement are often key economic drivers in regions, and these trips can see significant travel time benefits from strategies such as electronic toll collection, incident management, and work zone management.

Reliability refers to the consistency and predictability of travel time for people and goods. It is estimated that more than half of congestion experienced by travelers is caused by non-recurring events, such as weather conditions, work zones, special events, and major incidents and emergencies that are not associated with overall infrastructure capacity.22 Predictable, consistent travel times are highly valued by all users of the transportation system,from freight operators to transit users to commuting motorists. In a 2008 study of the economic impact of traffic incidents on businesses using North Carolina interstates, roughly three quarters of the businesses stated that shipment reliability was highly important because of a just-in-time manufacturing or inventory process.23 For individual travelers, unexpected congestion on the roads can also be costly as well, such as for workers trying to get to jobs on time, travelers trying to make airplane flights, or for working parents who need pick up their children at daycare on time to avoid late fees.

Charm City CirculatorBaltimore, Maryland Launched in January 2010, the Charm City Circulator has two routes serving downtown Baltimore and nearby residential neighborhoods. A third route is expected to launch sometime in 2011. The free service is targeted at downtown workers during the day and visitors during evenings and weekends. Buses operate every 10 minutes along linear routes designed to be easily understood. Routes are served by hybrid buses with distinctive designs and all stops are equipped with real-time bus arrival displays. As of June 2011, average daily ridership on the two routes was 7,700, far above initial ridership projections. For more information: http://www.charmcitycirculator.com/.

|

M&O strategies designed to improve system reliability also can support livability and sustainability by increasing safety, decreasing incidents, and reducing unnecessary delays that increase air pollution and create negative economic impacts on households and businesses. These strategies include the following, which may address all components of the multimodal transportation system:

- Incident and emergency management encompasses a wide range of activities performed by professionals from emergency response (police, fire, medical) agencies, emergency management agencies, transportation operators, towing companies, hazardous materials response agencies, coroners, and other organizations to prepare for, respond to, manage, and clear traffic incidents as well as natural and manmade disasters.

- Travel weather management involves

mitigating the safety and mobility impacts that adverse

weather conditions can have on the surface transportation

system. Three types of strategies—advisory, control, and treatment—are used to manage and operate the transportation system before, during, and after adverse weather (e.g., fog, snow, flooding, tornadoes, hurricanes) to mitigate the impacts on system users. - Work zone management—Work zones are estimated to cause approximately ten percent of all roadway congestion.24 In addition, maintenance work on rail systems causes unexpected and often prolonged delays for passengers and freight. Road work also has the potential to deteriorate safe mobility and access for pedestrians and bicyclists. Strategies to manage work zone impacts include traveler information, setting safe speed limits, pedestrian access plans, pre-positioning tow trucks to quickly clear incidents, innovative contracting, ensuring the appropriate geometric design to accommodate larger vehicles, and coordinating work zones on parallel routes.

- Planned special events management works to minimize unexpected delay due to sporting events, concerts, festivals, conventions, and other planned events that may have an impact on mobility due to increased travel demand and possibly reduced capacity. By effectively accommodating multiple modes of travel to and from the event, transportation managers can reduce the parking space needed and motorist delay caused by the significant surge in demand for travel and can mitigate the impacts of increased travel demand on communities near the event.25

Emphasis on M&O Strategies to Support Livability & SustainabilityLansing, Michigan The Tri-County Regional Planning Commission, the MPO for the Lansing, Michigan, metropolitan area, has found through surveys and other public involvement efforts that the public's highest priorities are maintaining mobility, preserving the system, and improving traffic flow through intersections and on major streets, while their lowest priority is system expansion. Given these results, the MPO is opting for a new approach to M&O that applies to all modes in congested corridors and considers a range of strategies, including road diets, traffic calming, ITS, more traditional traffic engineering treatments, and safety strategies. The MPO is also implementing approaches such as moving to continuous flow, lowering speeds, and reducing delays to optimize traffic while supporting livability, sustainability, and GHG reduction on principal arterials. For more information: http://www.tri-co.org/. |

In addition to improving reliability, M&O strategies can also promote livable and sustainable communities by contributing to efficient movement of people and goods on an ongoing basis, helping reduce unnecessary delay and minimize fuel consumption and costs. M&O strategies that improve system efficiency can help accommodate travel demand within the existing transportation footprint, reducing the need for roadway widening projects that can have adverse effects on surrounding communities, such as increasing barriers between neighborhoods in developed areas or injuring the beauty of the natural environment in more rural settings. Examples of these strategies include:

- Freight efficiency improvements include a variety of strategies focused on improving the efficiency of goods movement. For example, the Kansas City, Missouri, Cross-Town Improvement Project ties together truck and intermodal freight operations with traffic management systems to coordinate short-haul truck traffic movements between distribution centers, intermodal freight facilities, and industrial and commercial manufacturers and receivers. This reduces the number of empty truck movements within the metropolitan area.26 Freight haulers also benefit from strategies such as weigh-in-motion and electronic toll collection, which improve travel time.

- Automated toll collection reduces delays for drivers at toll booths through the use of electronic devices that can collect tolls as drivers pass below sensors. Open-road tolling collects tolls at normal driving speeds and allows drivers to bypass toll booths altogether. Faster toll collection causes less delay for drivers and reduces pollution from idling vehicles. For example, Maryland toll plazas were found to reduce harmful air pollutant emissions by 16 to 63 percent.27

- Adaptive traffic signal control is designed to reduce waiting time at traffic signals to reduce delays and emissions. Adaptive traffic signal control optimizes signals along arterials corridors in real time based on traffic conditions and system capacity using detection systems and optimization algorithms. A study conducted in 2000 of five cities with adaptive traffic signal control deployments demonstrated decreases in delay by 19 to 44 percent.28 Adaptive signal control in Toronto, Canada, was shown to reduce vehicle emissions by three to six percent and fuel consumption by four to seven percent.29 In London, England, TSP was combined with an adaptive signal control system with a resulting seven to 13 percent decrease in bus delay.30

- Reversible lanes, shoulder lanes, ramp metering, and other active traffic management techniques have been implemented to improve traffic throughput on heavily congested corridors as an alternative to capacity expansion. These improvements allow the system to accommodate peak direction flows without adding capacity that will sit unused for much of the rest of the day. For example, in Honolulu, Hawaii, arterial management is designed to support smooth traffic flow and includes use of contraflow lanes. In Washington, DC, some major arterials use overhead signals and reversible lanes to provide more inbound traffic lanes during morning rush hours and outbound lanes during the afternoon peak. On-street parking and standard lane configurations are used during off-peak periods, enabling good pedestrian and parking access for local businesses and neighborhoods. Multiple strategies may be implemented as part of an integrated corridor management (ICM) approach.31

Manage Travel Demand

Managing and operating the transportation system to improve livability and sustainability means not only reducing unnecessary travel delays but also managing travel demand in ways that support more transportation choices and more efficient use of the transportation system. Transportation demand management (TDM) includes a host of strategies that encourage travelers to use the transportation system in a way that contributes less to congestion, improves air quality, and enhances quality of life. TDM covers many aspects of trip-making, including:

- Whether to make a trip (through options such as telecommuting).

- What mode to use (by encouraging travelers to shift from driving along to ridesharing, transit, or walking and bicycling).

- When to make the trip (by encouraging shifts to off-peak periods).

- What route to choose (by encouraging use of less congested facilities).

TDM addresses travel behavior and habits, seeking to influence travelers’ decisionmaking before and during trips. Urban planning and design can complement these M&O strategies by encouraging development that reduces the distance between destinations and facilitates access by all modes.

TDM in Rural Recreational SituationsGlacier National Park, Montana TDM has a role to play outside of congested urban areas. In rural communities with large influxes of visitors, TDM can help manage demand to reduce impacts on the natural environment and surrounding communities while improving safety for residents and visitors. Glacier National Park is an example of how providing alternatives can do this. Since 2007, Glacier National Park has run a free shuttle system so visitors can safely travel through the park and avoid traffic and parking problems. In 2003, the park created the Red Bike Program to supply a fleet of bicycles for employees to use for work or recreational trips. The shuttles and bicycle fleet have expanded access, limited vehicular emissions, and reduced traffic by 20 percent. For more information, contact Susan Law, FHWA at susan.law@dot.gov. Lake Washington Corridor—State Route (SR) 520Seattle, Washington U.S. DOT’s Urban Partnership Agreement program includes implementation of four “Ts”: tolling, technology, transit, and telecommuting/TDM. One recipient of funding is the Puget Sound region, which will focus on the SR 520 corridor that links downtown Seattle to the Eastside area of Lake Washington. The project involves implementation of variable pricing on SR 520 to maintain free-flow traffic in the through lanes, discounted or free access for vehicles with three or more occupants, enhanced bus services, and real-time multimodal traveler information. The project also includes an active traffic management system that will be installed on SR 520 and I-90, which will consist of a series of electronic speed limit, lane status, and dynamic message signs over each lane on the SR 520 and I-90 bridges over Lake Washington. For more information: http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/Projects/LkWaMgt/. Commuter Rewards ProgramAtlanta, Georgia Atlanta has a commuter rewards program that since 2002 has offered participants $3 per day (up to $100) for each day they use a commuting alternative within a consecutive 90-day period. According to a 2003 survey, 64 percent of participants continue to use alternative modes 9 to 12 months after the program, even without an incentive. The program has experienced increased interest over the last several years, with more than 8,500 people enrolling in 2008—a threefold increase over 2007. The Clean Air Campaign in metropolitan Atlanta runs the commuter rewards program as part of a full suite of travel demand management activities. Overall, the TDM program prevents more than 200,000 tons of pollution annually in the region. Source: Center for Transportation and the Environment, The Clean Air Campaign Cash for Commuters Program Survey: Technical Report, 2010. |

Managing travel demand brings many benefits to communities and travelers. By introducing choice and flexibility into the transportation system, TDM reduces congestion and improves overall traffic flow. TDM also reduces stresses on transportation infrastructure by reducing both use of existing resources and the need to expand capacity. Reduced congestion and overall VMT from TDM strategies help to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Finally, TDM reduces travel expenses for individuals by reducing gas consumption and reducing the time spent in traffic.

Sample strategies to manage travel demand include:

- Ridesharing programs to promote carpooling and vanpooling. This strategy may include a ride-matching program that connects drivers with similar origins, destinations, and schedules. Employers will sometimes sponsor vanpools by subsidizing the vehicle costs. Some locations also provide reserved parking for carpools and vanpools. High-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes incentivize ridesharing with faster travel times. HOT lanes offer the same benefits to carpoolers while also allowing non-carpool vehicles to pay to use the lanes.

- Price signals such as variably priced toll lanes, parking pricing, or higher transit fares in the peak period for congested transit systems. These strategies encourage travelers to use higher occupancy modes (such as with HOT lanes) or to shift their travel to portions of the system with lower demand, whether that be by traveling at a different time, using a different route, or parking in a different location.

- Other incentives to encourage travelers to reduce vehicle travel demand. These can include subsidies for ridesharing or transit passes, activity-based promotions and commuter rewards, and preferred parking for rideshare vehicles. Guaranteed ride home programs can also incentivize alternative modes by alleviating concerns about being stranded if a traveler must stay late or leave early from work and cannot participate in his or her regular carpool, vanpool, or transit ride home. The programs generally reimburse participants for taxi fare or rental car on a day that they used one of these options and needed to return home unexpectedly during the day (such as for a sick child).

- Parking policies manage the supply and use of parking through strategies such as preferential parking for carpools or car sharing vehicles, and hourly pricing. Parking management can also reduce infrastructure costs by reducing the need to build parking spaces, which are costly to provide and do not in themselves contribute to community vitality. Use of existing parking space can be maximized through the use of shared parking, where users with parking demands that do not overlap share parking lots. For example, church parking lots may be used as park-and-ride lots during the workday, when church parking demands are low. Similarly, sometimes available parking is not immediately visible to motorists and occupancy sensors coupled with communications technologies can alert and direct drivers to such spaces.

- Car sharing is a form of short-term car rental that gives members access to vehicles stationed around the community. Vehicles can be reserved by the hour via smartphone, Internet, or call centers. Members get access to vehicles via a smart card and vehicles must generally be returned to the same location they are rented from. Car sharing is an alternative to vehicle ownership in places where people can use alternative modes to get to many or most of their destinations. The programs allow members to reduce the use of their own vehicles, reduce the number of vehicles they own, or eliminate vehicle ownership altogether. This reduces vehicle ownership costs for members while still providing access to a full range of mobility options. For communities, car sharing can help to reduce emissions and congestion. Car sharing programs exist in communities throughout the United States; as of July 2011, there were 26 programs with more than 560,000 members sharing more than 10,000 vehicles.32

- Telecommuting and flexible work schedules address travel demand by eliminating commute trips or shifting trips to off-peak periods. Less peak period travel reduces congestion, which improves air quality. These programs can also offer important quality of life benefits to participants by reducing the stress of commuting and by allowing workers to balance family and work needs, such as fitting their schedules to school schedules.

- Freight demand management involves strategies such as shifting a portion of trucks to off-peak travel times on appropriate facilities. The Chicago Metropolis 2020 Freight Plan included analysis of an alternative where 20 percent of truck traffic was shifted away from morning and evening peak periods and ten percent was shifted from the midday peak period to overnight. This resulting reduction in vehicle hours traveled was estimated to yield an estimated $1.4 billion in direct savings to Chicago metropolitan area businesses.33 This strategy was estimated to not only significantly reduce delay for commercial vehicles but also provide a boost to the regional economy. (Note: The ability to shift truck traffic to off-peak delivery times, though, is largely dependent on whether freight receivers are available to receive goods shipments at off-peak times.)

- Active transportation and demand management is an emerging concept that integrates the concepts of active traffic management and travel demand management. It is a proactive approach to dynamically manage and control the demand for and available capacity of transportation facilities, based on prevailing traffic conditions, using one or a combination of real-time and predictive operational strategies.34

21st Century Parking ManagementSFpark and ParkPGH Real-time parking information can help reduce travel delay and emissions (and driver frustration) by reducing the need for drivers to circle around looking for parking. Two recent programs in this area are: Begun in 2010, SFpark is a demand-responsive parking pricing and management system. The pilot effort provides real-time parking availability information for on- and off-street parking and also incrementally raises or lowers parking prices based on demand to maintain a minimum level of parking availability. SFpark uses parking meters that accept credit cards and mobile device applications, text messages, and electronic display signs to help improve parking efficiency. For more information, go to: http://sfpark.org/. In Pittsburgh’s downtown cultural district, ParkPGH provides real-time information on available parking. An application, website, and call-in phone number all allow travelers to get current information on the number of available spaces in all nearby garages, with data updated each minute through a feed from the gate system at each garage. This makes it easier for the public to access cultural institutions and may reduce travel delay and emissions by avoiding searches for available parking. For more information, go to: http://parkpgh.org/. |

Provide Information to Support Choices

Managing and operating a multimodal transportation system for improved livability and sustainability involves providing timely and accurate information to system users on transportation conditions. With a greater level of awareness, travelers and freight carriers can make better decisions about when or if to travel, which route to take, and which mode to choose. This contributes to livability through greater predictability of services, more options for avoiding delay, and a higher-quality travel experience. In addition, this information can save lives and reduce injuries by informing the public when road conditions are unsafe and enabling commercial vehicle drivers to locate available parking for critical rest periods. Providing traveler information that helps system users avoid congestion and facilitates taking transit, walking, and bicycling significantly supports environmental sustainability by reducing motor vehicle emissions and infrastructure needs. Traveler information is vital to managing the surge in travel demand for special events and is used to help attendees plan their travel before the event, en route to the event, and after the event. Traveler information is also crucial in diverting traffic or passengers during an incident, adverse weather, and active work zones.

Cross-State Traveler Information, North/West Passage Corridor (Interstates 90 and 94)Interstates 90 and 94 between Wisconsin and Washington are major corridors for commercial and recreational travel. The extreme winter weather conditions prevalent in the states within this corridor pose significant operational and travel-related challenges. Through the North/West Passage Corridor, the nine States along this corridor are working together to address shared transportation issues related to traffic management, traveler information, and commercial vehicle operations along the corridors. Projects completed thus far include the development of a traveler information website for the entire corridor (www.i90i94travelinfo.com) and defining a common set of phases to describe events (incidents, weather) that all States have agreed to use for the corridor. Previously, each State had its own phrases, which made sharing information across states more difficult. |

The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) provides an extensive website that supplies travelers with real-time traffic flow data, estimated travel times, wait times on popular routes, and traffic camera images updated every 1.5 minutes. WSDOT also operates a 511 telephone service that provides contact information for rail, bus, ferry, and airline operators, as well as construction and traffic incident information. All of this information is managed through a state-of-the-art speech recognition program that allows callers to ask for specific information about travel times or traffic flow on specific highways.35 The Niagara International Transportation Technology Coalition (NITTEC) provides a similar tool for travelers in its member jurisdictions in the form of a regional transportation information clearinghouse. In this case, partner agencies within NITTEC pool transportation information to provide travelers with comprehensive views of the region and a greater level of customer service than any single agency within NITTEC could provide.36 In Singapore, travelers can now access multimodal trip information from on their mobile phones with a public service known as MyTransport.SG offered by the Land Transport Authority. Using location-based service technology to detect the user’s location, MyTransport.SG provides real-time bus information, locations for light rail and premium bus service, and a trip planner that shows how to get to a destination via public transportation. For the motorist, it also provides real-time availability at parking lots in a number of areas, live traffic cameras, and up-to-date traffic information including locations of incidents and work zones.37

Comparative Travel Times for Car Versus TrainSan Mateo County, California On U.S. 101 in San Mateo County, California, variable message signs display real-time highway travel times to downtown San Francisco alongside transit travel times on the nearby Caltrain commuter train service. Transit information also includes the departure time at nearby park-and-ride stations. This information allows travelers to make modal decisions en route, depending on the conditions. The signs are an integral part of Caltrans’ multimodal integrated corridor management approach. Source: Mortazavi et al., Travel Times on Changeable Message Signs, 2009. |

In Japan, motorists can access real-time traveler information in their vehicles using the vehicle information and communication system (VICS). VICS uses roadside infrastructure to detect congestion and then broadcasts traffic information by character multiplex, radio beacons, or optical beacons to vehicles. It can be displayed in the vehicle as text or on a map.38

Support Placemaking

As both urban and rural jurisdictions increasingly seek development that enhances community vitality, the concept of “placemaking” continues to increase in importance. Placemaking emphasizes the connections between land use and transportation, as well as urban design and operations. Rather than just building roads to provide access and mobility, this approach to transportation planning, design, and operations emphasizes context-sensitive solutions that integrate transportation, building, and landscape design to create a “sense of place.”

| “Placemaking is a multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and management of public spaces. Put simply, it involves looking at, listening to, and asking questions of the people who live, work and play in a particular space, to discover their needs and aspirations. This information is then used to create a common vision for that place. The vision can evolve quickly into an implementation strategy, beginning with small-scale, do-able improvements that can immediately bring benefits to public spaces and the people who use them.” — Project for Public Spaces |

Through coordinated land use, design, and operations strategies, placemaking can help a community tell a story about its history and promote the type of development and transportation facilities that residents prefer for their community. Virtually no group of residents promotes a future community vision consisting of a transportation system allowing only for automobile travel or promoting higher speeds and vehicle volumes on local streets. As a result, placemaking generally supports development that focuses vehicle traffic on appropriate arterials, supports transit where feasible, provides a comfortable walking and bicycling environment to local destinations, and promotes livability and sustainability principles.

M&O strategies can work hand-in-hand with community development by improving roadway network connectivity, access management, reliability, safety, and land use and transportation coordination. As a result, M&O strategies can also play a vital role in developing unique places that support community vitality and reflect the desired character of communities. Successful placemaking often depends on selecting appropriate M&O strategies that complement planning and design efforts and that implement local visions identified through community outreach.

Specific M&O strategies that support placemaking efforts and also have beneficial impacts on mobility, livability, and community design include:

- Road diets, or “right-sizing,” which combine M&O elements of traffic calming and complete streets to support livability and sustainability, promote transportation choices, and support placemaking. Road diets reduce the number of through travel lanes on a roadway and repurpose that right of way for other uses, such as improved pedestrian and bicycle facilities, on-street parking, and/or landscaping. Although many road diet projects involve nothing more than restriping, they have been found to enhance the surrounding environment, reduce crashes for all modes, promote non-motorized transportation use, and provide cost-effective traffic calming benefits.

- Network connectivity enhances livability and sustainability goals by supporting a variety of transportation options for travelers. A well-connected street grid provides direct routes for bicyclists and pedestrians; a variety of routes for vehicles to help reduce congestion and provide alternative routes in case of incidents, construction, or special events; and multiple routes that can be designed to “sort” traffic and provide different travel environments for different modes and trip types. Although changes to network connectivity frequently involve capital investments such as building new roads or paths, M&O strategies can also improve connectivity. For example, converting one-way streets to bidirectional travel can increase connectivity and access while also providing traffic-calming benefits.

- Roundabouts, an alternative to traffic signals that offer multiple safety, operational, and placemaking benefits. From an operations and livability perspective, roundabouts can slow traffic while increasing capacity, reduce queuing and congestion, reduce the frequency and severity of collisions, and minimize potential vehicle-pedestrian conflicts. Roundabouts can also serve in a placemaking role by acting as a gateway treatment and a focal point for businesses or by housing distinctive landscaping or artwork within the center island. Several States and communities consider roundabouts as an equal or better replacement for signals.

- Truck delivery parking that supports commercial retail stores and other businesses valued in livable communities. Appropriately designed commercial streets and truck delivery parking areas near businesses enable businesses that rely on truck deliveries to receive necessary goods in a timely manner. Appropriately designed truck delivery parking, particularly curbside parking, also reduces double parking, helping to reduce roadway congestion while improving safety for pedestrians, bicyclists, and motorists.

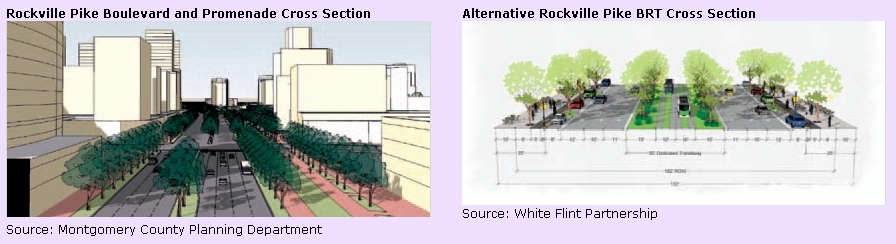

White Flint Sector PlanMontgomery County, Maryland White Flint was first proposed as an urban, mixed-use center more than 30 years ago, when Metrorail service was extended to the area. Although the area had ample transit access, White Flint's suburban street layout made direct connections between transit and other destinations difficult. In addition, pedestrian and bicycle conditions were poor and the Rockville Pike acted as a barrier in the community. The White Flint Sector Plan aims to transform the area into a vibrant transit-oriented development through a variety of placemaking and management strategies, including:

For more information: http://www.montgomeryplanning.org/community/whiteflint/. |

Use Balanced Performance Measures

Caltrans Smart Mobility Framework“Smart Mobility moves people and freight while enhancing California’s economic, environmental, and human resources by emphasizing: convenient and safe multimodal travel, speed suitability, accessibility, management of the circulation network, and efficient use of land.” The Caltrans Smart Mobility Framework was developed through a partnership between Caltrans, the California Department of Housing and Community Development, and the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research. The framework establishes six Smart Mobility goals that are supported by 17 Smart Mobility Performance Measures. The goal of each measure is to demonstrate the relationship between specific land use and transportation decisions and consequent effects on economic, social, and environmental conditions. The performance measures evaluated and targets used are tailored to address the needs of seven specific “place types” (e.g., urban, suburban, rural, special use). Certain performance measures, such as collision rates by mode, speed suitability, travel time, and consistency receive high priority for all place and facility types, while the priority of measures such as network performance optimization and speed management, may vary by facility and place type. Use of reasonable professional judgment is recommended when applying Smart Mobility performance measures. For more information: http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/tpp/offices/ocp/smf.html. |

The performance measures transportation agencies use to evaluate a transportation system and the ways that these metrics are defined and measured significantly impact how the transportation system is managed and operated. Incorporating livability into transportation agencies’ performance frameworks necessitates rethinking auto-oriented mobility goals and measures. Effectively evaluating the impact of M&O strategies on livability and sustainability requires new performance measures that are focused on efficient movement of people and goods rather than vehicles and that consider the effects of the transportation network on the full range of livability and sustainability outcomes (e.g., social equity, economic impacts, environmental quality).

For instance, as part of the Federally-required CMP in metropolitan areas larger than 200,000 people, some regions are moving from traditional volume/capacity-based congestion measurement to a broad range of congestion measures that address community concerns, such as multimodal transportation system reliability, access to multimodal travel options, and access to traveler information.39 These measures help regions consider a broader range of solutions to congestion, including more M&O strategies.

When implementing these performance measures, agencies may need to find new data sources to consistently evaluate some measures. For example, many agencies lack the data to calculate multimodal level-of-service and travel time reliability measures.

Livability performance measures may be context specific and defined at the community scale. For example, the different needs of urban and rural transportation system users influence how they define livability and the priority they apply to different travel modes and performance metrics. Although specific metrics and methodologies vary by agency, livability and sustainability are generally implemented using the triple bottom line approach of measuring impacts related to economics, environment, and equity. Programs that have successfully integrated M&O, livability, and sustainability in their performance management process appear to share several characteristics, including flexibility or context sensitivity, public involvement in measure selection and development, multidisciplinary or interagency collaboration, and scenario planning or other practical applications of measures. Other key factors to consider when selecting measures include:

- Select measures that directly relate to broader agency and stakeholder goals.

- Measures should be outcome-based.

- Consider data availability and cost.

- Measures should be objective, easily understood, and reproducible.

Table 3 illustrates potential M&O performance measures related to each of the livability principles of the Federal Partnership for Sustainable Communities.

| Livability Principle | M&O Performance Measure |

|---|---|

| Provide more transportation choices |

|

| Promote equitable, affordable housing |

|

| Enhance economic competitiveness |

|

| Support existing communities |

|

| Coordinate policies and leverage investment |

|

| Value communities and neighborhoods |

|

Collaborate and Coordinate Broadly

Creating livable and sustainable communities requires carefully balancing the needs of multiple segments of a population in the current generation as well as future generations to ensure a healthy, vibrant quality of life for all. To achieve this balance, these diverse perspectives must be heard and incorporated into the decisions regarding the management and operation of the transportation system through full collaboration and coordination of a broad range of stakeholders.

User-Friendly Resources to Promote Walking

Published by Portland Metro Regional Government and funded by a health provider, Walk There! is a guidebook with 50 treks in and around Portland and Vancouver. |

In the Netherlands, more than 300 companies, government agencies, and knowledge institutes joined together in 2005 as part of the Transumo Foundation to lead a transition toward sustainable mobility in the country. Motivated by the inefficiency of the current transportation system and the policies that impede sustainable development, the group began the TRADUVEM project to organize a broadly collaborative transition process that brings together traffic management and transition management professionals as well as other stakeholders to define what sustainable transportation should look like and how to achieve the transition to that vision. TRADUVEM is responding at least in part to a lack of integration between public and private entities, levels of organizational management, regions, and management and infrastructure planning that has held back widespread innovation in traffic management. The project aims to work toward innovation in traffic management and achievement of the following paradigm shifts:

- “From management of the ‘status quo’ to management of variation.

- From traffic management to network management.

- From reactive to proactive management.

- From external control to hybrid (external and internal) control.

- From emphasis on throughput to emphasis on sustainability (throughput, safety, environment, livability, etc.).”40

In Portland, Oregon, the MPO hosts a Regional Travel Options Subcommittee of 20 agencies and stakeholder organizations that work together to “promote and support travel options to help cut vehicle emissions, decrease congestion and create a healthier community.”41 In 2008, the subcommittee helped develop the Regional Travel Options 2008- 2013 Strategic Plan that defines the goals, objectives, and strategies for the Portland region’s travel options program. Projects resulting from the plan receive funding through Metro’s transportation improvement program. This highly active program creates user-friendly resources for the community to encourage walking, bicycling, and ridesharing.

The management and operation of a regional or statewide transportation system also requires coordination and collaboration among multiple agencies and jurisdictions. A seamless travel experience for the public requires that operating agencies work together to provide comprehensive traveler information, coordinated traffic signals, and efficient management of incidents, special event, or work zones that affect neighboring jurisdictions. High levels of interagency collaboration occur throughout the United States, including the NITTEC, a consortium of 14 agencies in the Niagara region of New York and Ontario that have come together to work toward a common mission to “improve regional and international transportation mobility, promote economic competitiveness, and minimize adverse environmental effects related to the regional transportation system.”42 This ongoing collaborative effort and others are described in the FHWA report The Collaborative Advantage: Realizing the Tangible Benefits of Regional Transportation Operations Collaboration.43 By coordinating transportation management with regional partners, member organizations can improve the efficiency and reliability of transportation services while using fewer resources.

Coordination and collaboration can also occur at the project level. Coordinating neighborhood traffic management program studies and projects to address whole districts and the impact of the overall system is another opportunity to promote livable and sustainable communities.44

You will need the Adobe Acrobat Reader to view the PDFs on this page.

18 Hallmark, Shauna, et al., "Evaluation of Gateway and Low-Cost Traffic-Calming Treatments for Major Routes in Small Rural Communities," for Iowa DOT and U.S. DOT, November 2007. Available at: http://www.ctre.iaState.edu/reports/traffic-calming-rural.pdf. [ Return to note 18 ]

19 U.S. DOT, FTA, Bus-Only Shoulders in the Twin Cities, June 2007. Available at: http://www.hhh.umn.edu/img/assets/11475/Bus%20Only%20Shoulders%20Report%20FINAL.pdf. [ Return to note 19 ]

20 Dowling, Richard et al. Multimodal Level of Service Analysis for Urban Streets. National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 616, 2008. Available at: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_616.pdf. [ Return to note 20 ]

21 Boyle, Dan, Practices in the Development and Deployment of Downtown Circulators: A Synthesis of Transit Practice, Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Synthesis 87, 2011. Available at: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_syn_87.pdf. [ Return to note 21 ]

22 U.S. DOT, FHWA, Traffic Congestion and Reliability: Trends and Advanced Strategies for Congestion Mitigation, 2005. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/congestion_report/index.htm. [ Return to note 22 ]

23 Khattak, Asad, Yingling Fan, and Corey Teague. "Economic Impact of Traffic Incidents on Businesses." Transportation Research Record Vol. 2067 (2008): 93-100. [ Return to note 23 ]

24 U.S. DOT, FHWA, Traffic Congestion and Reliability: Trends and Advanced Strategies for Congestion Mitigation, 2005. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/congestion_report/index.htm. [ Return to note 24 ]

25 U.S. DOT, FHWA, Managing for Planned Special Events Handbook: Executive Summary, 2007. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop07108/index.htm. [ Return to note 25 ]

26 U.S. DOT, FHWA, Identifying How Management and Operations Supports Livability and Sustainability Goals, White Paper, April 2010. [ Return to note 26 ]

27 U.S. DOT, ITS Joint Program Office, Investment Opportunities for Managing Transportation Performance through Technology, January 2009. Available at: http://www.its.dot.gov/press/pdf/transportation_tech.pdf. [ Return to note 27 ]

28 U.S. DOT, FHWA, What Have We Learned About Intelligent Transportation Systems?, December 2000. Available at: http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/jpodocs/repts_te/13316.pdf. [ Return to note 28 ]

29 Greenough and Kelman, “ITS Technology Meeting Municipal Needs—The Toronto Experience,” Paper presented at the 6th World Congress Conference on ITS, Toronto, Canada, November 8-12, 1999. Summarized in the U.S. DOT ITS Joint Program Office, ITS Benefits Database. [ Return to note 29 ]

30 Hounsell, Nick, “Intelligent Bus Priority in London: Evaluation and Exploitation in INCOME,” Paper presented at the 6th World Congress Conference on ITS, Toronto, Canada, November 8-12, 1999. Summarized in the U.S. DOT ITS Joint Program Office, ITS Benefits Database. [ Return to note 30 ]

31 U.S. DOT, ITS Joint Program Office, “Integrated Corridor Management Systems.” Available at: www.its.dot.gov/icms/index.htm. [ Return to note 31 ]

32 Shaheen, Susan and Adam Cohen. Carsharing. Innovative Mobility Research, University of California, Berkeley. Available at: http://www.innovativemobility.org/carsharing/index.shtml. [ Return to note 32 ]

33 Economic Development Research Group, Inc., "Assessing the Economic Impacts of Congestion Reduction Alternatives," in Chicago Metropolis Freight Plan, Chicago Metropolis 2020, 2004. Available at: http://www.edrgroup.com/library/freight/the-chicago-metropolis-freight-alternatives.html. [ Return to note 33 ]

34 U.S. DOT, FHWA, Synthesis of Active Traffic Management Experiences in Europe and the United States, May 2010. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop10031/index.htm. [ Return to note 34 ]

35 U.S. DOT, FHWA, Livability Initiative Case Studies, July 2010. Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/livability/case_studies/. [ Return to note 35 ]

36 U.S. DOT, FHWA, The Collaborative Advantage: Realizing the Tangible Benefits of Regional Transportation Operations Collaboration, August 2007. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/benefits_guide/index.htm. [ Return to note 36 ]

37 Land Transport Authority, "PublicTransport@SG A Delightful Journey, A Greener Choice," 2009. Available at: http://www.publictransport.sg/publish/ptp/en.html. [ Return to note 37 ]

38 Greenough and Kelman, “ITS Technology Meeting Municipal Needs—The Toronto Experience,” Paper presented at the 6th World Congress Conference on ITS, Toronto, Canada, November 8-12, 1999. Summarized in the U.S. DOT ITS Joint Program Office, ITS Benefits Database. [ Return to note 38 ]

39 U.S. DOT, FHWA, Congestion Management Process: A Guidebook, April 2011. Available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/congestion_management_process/cmp_guidebook/chap01.cfm [ Return to note 39 ]

40 Immers, Ben, Isabel Wilmink, Paul Potters, Transitions Towards Sustainable Traffic Management, 2007. Available at: http://www.transumofootprint.nl/Library/document.aspx?ID=389. [ Return to note 40 ]

41 Portland Metro, Regional Travel Options 2008-2013 Strategic Plan, 2008. Available at: http://library.oregonmetro.gov/files/rto_strategicplan_6-10-08.pdf. [ Return to note 41 ]

42 NITTEC, Niagara International Transportation Technology Coalition homepage, http://www.nittec.org/. [ Return to note 42 ]

43 U.S. DOT, FHWA, The Collaborative Advantage: Realizing the Tangible Benefits of Regional Transportation Operations Collaboration, August 2007. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/benefits_guide/index.htm. [ Return to note 43 ]

44 Dock, Frederick C., "Pasadena's Next Generation of Transportation Management," ITE Technical Conference and Exhibit, 2010. [ Return to note 44 ]