Disseminating Traveler Information on Travel Time Reliability

CHAPTER 4. DEPLOYMENT OF THE TRAVEL TIME RELIABILITY LEXICON

This chapter provides information to transportation agencies with respect to use cases, data needs, delivery platforms, and other important considerations when assessing the potential use of Travel Time Reliability (TTR) information in their jurisdiction.

USE CASES FOR TRAVELERS

As discussed previously, travelers might find TTR information useful in a variety of situations related to trip planning. As agencies consider disseminating TTR information to their system users, they could consider various scenarios in which travelers and other stakeholders might find that information valuable and present it as such for ready use. These scenarios, which are by no means exhaustive, include the following:

- Individual Trip Planning – Habitual: Travelers may find TTR information valuable when planning habitual trips, such as daily commutes. TTR information may be particularly valuable when an individual is new to an area and unfamiliar with routes and typical travel times. They may also find it beneficial when moving to a new neighborhood or corridor within a community and need to assess commute times in new corridors. Explaining the potential use of the information for these habitual trips could be beneficial to the traveler and increase the overall value of the information to the target audience.

- Individual Trip Planning – Unfamiliar: Travelers may find TTR information useful for pre-trip planning immediately prior to departure or to make decisions about departure time and/or mode based on real-time and historical travel time trends, especially if traveling at a time or to a destination that is not typical. Explaining the value of TTR information for unfamiliar trips and how someone might use the information could help increase the overall value and usage of the information by the target audience.

- Individual Trip Change: Travelers may find TTR information helpful en-route and consider changing their trip while in progress prior to a route or mode choice point (again based on both real-time and historical information regarding particular routes at particular times of the day). However, it is important to note that the traveler should not be encouraged to access the information in a moving vehicle as this increases distraction in the driving environment.

- Alternate Route Comparison: Travelers may need to decide between alternate routes for either familiar or unfamiliar trips. Making TTR information available for facilities with alternate routes might improve the usability of the information by the target audience.

- Employment Center Location: Corporations or large employers could utilize TTR information when considering employment center locations within corridors with reliable travel times for employees. Presenting TTR trends for facilities along with comparisons of regional facilities can make this information useful to these stakeholders.

- Overall System Reliability: Agencies can use TTR information and the Lexicon phrases to provide stakeholders and decision makers with valuable information on system reliability. This information can be used to assess the priorities of future projects as well as to assess the impacts of projects and operational strategies for corridors and the system as a whole. The target audiences for this information presentation could include, but not be limited to, regional planning organizations; transportation agency decision makers; local chambers of commerce; economic development organizations; travel and tourism organizations; local entities such as school districts and universities; and more.

DATA NEEDS

For an agency to present TTR information to system users, it will need to have historical traffic datasets as a source for determining the TTR calculations. These calculations are then utilized by information dissemination platforms so that travelers can make informed decisions about their trip. To ensure compatibility across all platforms and to provide information that can be easily understood by system users, historical traffic datasets benefit from the following:

- Average segment-based travel time data with origins and destinations corresponding to the majority of entry/exit points along each corridor by direction. These average values are used as the “typical” travel time for display in the traveler information applications.

- For each of the segments in a corridor and for each aggregation period, the 95th percentile travel time for use in determining the worst-case travel times.

- Travel time data aggregated by day of week in at least hourly intervals for a 6-month period or more. The aggregation time (e.g., 15 minutes, hourly) limits the resolution of the departure and arrival times in the traveler information applications.

- The most recent historical dataset possible in order to reflect the current traffic conditions as accurately as possible.

Based on the availability of data, as well as source, time-frame, and format, agencies likely will need to manipulate the data to generate a dataset that can be mined to calculate TTR information and disseminate that information to the traveling public. To illustrate the type of data manipulation that might be necessary, the manner in which the project team handled travel time and speed data from Houston is described below. It is important to note that the volume and type of data available in Houston is not typical, given that the region collects and manages its own flow data. Many other locations obtain flow data from third-party sources, which may have different levels of granularity. The manipulation and summary of those data likely will differ considerably from that in Houston; however, the format of the final resulting dataset would be similar.

The Houston region has an extensive deployment of Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) based sensors installed throughout each of the study corridors, which provide speed and travel time information through the region’s traffic management center, Houston TranStar™. The source of the Houston study data was the information collected by these sensors that utilize either Bluetooth or toll-tag-based re-identification for estimating travel times. The sensors are operated by the Texas Department of Transportation, which provided the data for the study’s usage for the I-10 Katy, I-10 Katy Managed Lanes, Westpark Tollway, I 45 North, I-45 North High-Occupancy Vehicle (HOV), and Hardy Toll Road study corridors.

The origins and destinations for each travel time segment were based on the locations of the roadside sensors. In most cases, the sensors were located near major entry and exit points along the corridors with 1- to 3-mile spacing. The software internal to Houston TranStar™ collects and processes the travel time data in both real-time and historically, and aggregates the data into 15-minute summaries by day of week. For each 15-minute period and for each day of the week, the dataset contained a location identifier (including the roadway name, direction of travel, origin cross street, and destination cross street), a timestamp indicating the time of the summary, an average travel time, and a 95th percentile travel time.Delivery Platform Data Interface Technical Description

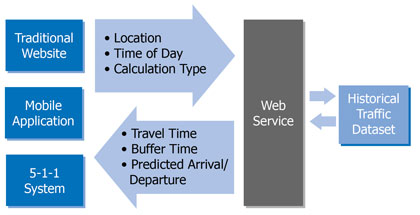

There are a variety of approaches to disseminating TTR information to travelers depending on the delivery platform that an agency intends to use for the dissemination or which they already manage. For example, a backend architecture for a pre-existing traveler information website can provide a data interface framework for any of the three information delivery platforms included in the Lexicon. Additionally, a web Application Programming Interface (API) can be developed to allow other applications to query the historical datasets that are developed for a region. Typically, the delivery platform (e.g., a traditional website, mobile application, 511 system) can make queries to a web interface to obtain the traffic conditions data.

To initiate a query to the web service, a client makes a call to a web address with the following parameters included:

- Starting Location ID.

- Ending Location ID.

- Time of Day.

- Date of Travel.

- Departure or Arrival Calculation.

- Lexicon Phrase Selection.

Based on the information passed via the parameters, the web service queries the appropriate historical dataset and returns a string of text containing the approximate travel time, buffer time, and predicted arrival or departure time. The different information channels are then able to relay this information in an appropriate format (e.g., webpage via the website and mobile application, via 511). A diagram of a typical web service architecture is shown in Figure 3. This particular architecture was used in the research study, but can be replicated for a particular location.

Figure 3. Graphic. Web service architecture.

Note that this web service architecture may vary depending on the traveler information website or service currently operated by an agency.

INFORMATION DELIVERY PLATFORMS

The research study tested three information platforms: a mobile application provided via smartphone, a traditional website, and a 511 telephone service.

- The mobile application was the platform most preferred by users in the study. This format can be the most convenient option for users to find TTR information at the point when they may be most likely to want it (i.e., just as they are beginning a trip). Designing the application so that users can enter and save personalized information such as their most-used departure point can help to maximize utility of this platform. Drivers should be encouraged to not enter any information while operating a vehicle.

- A traditional or mobile website may offer more options for customizing user inputs and/or output formats. This information platform ranked second in preference among study participants.

- The 511 telephone service was least preferred by study participants. It is therefore not recommended that an agency develop a 511 system solely for the purpose of providing TTR information. However, if an agency already has a 511 system for travel information and develops other platforms (e.g., mobile application, mobile website, traditional website) for deploying TTR information, the mechanism for transferring that TTR information to the 511 system is fairly straightforward.

COMBINING REAL-TIME AND RELIABILITY INFORMATION

The original research conducted in the Strategic Highway Research Program 2 (SHRP2) L14 research project indicated that travelers consider real-time travel time information to be valuable and even necessary in addition to historical data when planning trips. However, this project did not assess the viability and/or best approach to combining those sources of information. Thus, additional research is needed to determine how best to combine real-time and historical travel time information to provide the most useful and accurate information to travelers. Some regions are beginning to provide this comparison information and future research could benefit these and other regions in ensuring that these two forms of information are combined in an effective manner to optimize the user travel experience.

If an agency determines that TTR information will be valuable to its system users, it is important to clearly explain to them the difference between real-time information and TTR information. It is highly likely that system users will be familiar with existing real-time traveler information for the region from the plethora of sources available to them across providers and information dissemination platforms. They also are highly likely to be very familiar with the roadway network in the region, especially for their regular commute route. They may not intrinsically understand what TTR information is telling them, so an explanation is important for comprehension. Furthermore, providing examples of how travelers might use TTR information for trip planning (e.g., unfamiliar trips, familiar trips at unusual times, etc.) may help increase awareness and overall use of the information by travelers. If the transportation agency already provides real-time traveler information, then comparing the two types of information in a side-by-side comparison might help with comprehension and usage.