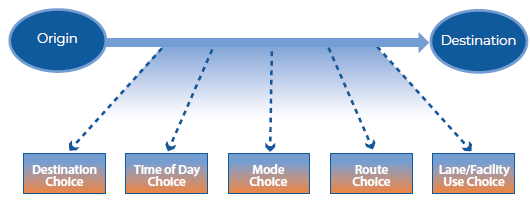

Expanding Traveler Choices through the Use of Incentives: A Compendium of Examples1. IntroductionRichard Thaler's 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics generated increased interest in behavioral economics and, in particular, how we make choices. The general premise of Thaler's work is that individuals often make choices based on habit or with limited rationality, leading to systematic errors resulting from inattention and procrastination. We see this frequently in transportation decisions when individuals make mobility choices that reflect an unwillingness to try different ways of reaching the places, people, and things that they need to access. This is true even when the evidence suggests that available mobility options could lead to better outcomes for individual travelers and for the larger community. Standard economic approaches to changing traveler behavior that rely on individuals making rational economic choices based on pricing have proved less effective for motivating and sustaining changes in traveler behavior. (Avineri, 2009) "Evidence from behavioral, cognitive and social sciences is painting a more complex picture of decision-making processes. In real life the behavior of travelers is typified by limited cognitive resources—for example, difficulties in processing large amounts of data—bounded rationality (in many cases we fail to make the best choices) and emotional and habitual behavior." (Avineri, 2009) This primer describes how transportation agencies and other mobility services can address recurring and non-recurring congestion through "nudges" that incorporate behavioral economic concepts and encourage travelers to shift their mode, time of travel, or route. The primer provides case studies based on programs offered by State, regional, and local transportation agencies, universities and research institutions, and within the private sector that provide incentives designed to encourage individuals to consider alternatives. In addition to reducing congestion, these incentives can lead to improvements in air quality through reduced emissions, reductions in energy consumption, safer roadways, and more livable and sustainable communities. Incentives for modifying traveler behavior have been in use for many years. For example, some employers provide convenient (or free) parking for carpool vehicles, some subsidize public transportation, some compensate employees for travel time while using mass transit, and some offer on-site services (e.g., child care, laundry, exercise equipment, dining facilities) to reduce extra trips. Employers may provide secure storage for bicycles and have shower facilities for employees who ride bicycles to work and offer flexible schedules and telecommuting options so that employees can manage their work schedules and travel patterns to avoid peak congestion periods. These employee benefits are "nudges" or incentives to encourage (or permit) employees to consider choices that benefit employers (they attract and retain good employees), employees (they have greater flexibility and more mobility choices), and the community at large (fewer people driving alone during peak periods). Recent technology has opened up many more opportunities for travelers to modify their trips and transportation managers to influence travel in real-time in ways that previously were not possible. The ability for transportation managers to effect real-time shifts in traveler choices enables them to proactively manage the system and customize incentives to address the dynamic nature of non-recurring events. For example, traffic management centers (TMCs) can incentivize shifts specifically for short-term events such as a major incident, work zone, special event, or poor air quality day. Smartphone applications can provide information to travelers prior to their trips and en-route to help them avoid congested routes or events using a combination of public and private sector data and advanced analytics. Additionally, global positioning system (GPS) tracking on smartphones enables incentive program administrators and travelers to automatically track behavior and provide incentives accordingly. Advanced computing capabilities support predictive traffic information that can be combined with incentive programs to reduce congestion. Incentivizing travelers to make dynamic shifts to their mode, time of travel, or route before and during their trips is a core concept of active transportation and demand management (ATDM). In particular, these incentives focus on the "active demand management" element of ATDM. Figure 1 illustrates the traveler decisions that ATDM strategies target to help manage overall system performance in real-time.  Figure 1. Illustration. Active Transportation and Demand Management strategies work to dynamically influence multiple traveler decisions across the trip.1 Source: Federal Highway Administration. This primer presents several specific examples of how these "nudges" have been implemented in ways that are designed to encourage travelers to consider alternative modes, routes, or times. The number and variety of "nudges" suggest that many opportunities exist for changing traveler behavior. The primer provides a detailed description of several of these programs, which are offered by both transportation agencies as well as private sector entities (e.g., employers, retailers). Some examples of incentives for encouraging alternative mode choices include:

Some examples of incentives for encouraging time of departure changes include:

Some programs that offer incentives for eliminating travel altogether include a reward for a reduction in total vehicle miles traveled (VMT) during a specified time period relative to previous periods. Others aim to incentivize travelers to change their routes by including rental credits for assisting with the redistribution of shared-use electric vehicles so that they have access to recharge stations and are available for other travelers. Studies associated with incentivizing (or permitting) travelers to shift their travel times away from peak periods so that they avoid—and therefore reduce—peak period congestion were pervasive in the literature and appeared to have been effective at least in the near term. The nudges come from multiple directions, including employers that permit employees to work flexible hours (and weeks) so that they reduce or eliminate trips made during peak periods as well as a variety of rewards or points awarded for travel during off-peak periods. Other, more localized or focused nudges encourage or reward eliminating or reducing the use of vehicles and either reducing trips or using other modes (including non-motorized options) to complete trips. These nudges can come in the form of rewards for using alternatives to private vehicles or penalties (often in the form of pricing) for parking private vehicles in areas that are served by alternative travel modes. In summary, evidence is growing that travelers are responsive to appropriately designed and implemented incentives that encourage behavioral changes that reduce dependence on SOVs or on traveling during peak demand periods. Examples are described in greater detail in this primer. The primer is organized around the categories of choices described above. However, many of the incentives are designed to influence travelers' choices in multiple areas (e.g., time, mode, route) simultaneously. The primary intent of the primer is to stimulate thinking about how best to influence traveler behavior by describing the current state of the practice with the hope that others will build on this foundation. 1 Federal Highway Administration, Active Transportation and Demand Management (ATDM) Introduction, Presentation. Last modified on October 4, 2017. Available at: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/atdm/knowledge/presentations/atdm_overview/index.htm. [ Return to note 1. ] |

|

United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration |

||