Model Systems Engineering Documents for Central Traffic Signal Systems

Chapter 6. Purchasing a System Using Systems Engineering Documents

Traditional Approaches are Risky for Technology Projects

Most agencies buy systems by first exploring the marketplace to identify which technologies and products have the features they want, and then work from the sample specifications provided by the vendors of those technologies and products. They prepare plans and specifications, and then go out for bid. They then select the lowest responsible bidder, but they determine whether a bidder is responsible based on reputation or product affiliation. The bidder receives the contract, and then as part of mobilization, provides a material submittal, which includes product cut sheets describing what materials they intend to provide on the project.

For technology projects, prospective bidders select system and product providers based on cost or standing relationship, and usually require those providers to provide technical information needed to support the bid, and materials to include in the submittal.

The agency usually accepts the submittal unless it points to technologies and products different from what they had explored. If the contractor proposed a different provider, a negotiation begins where the contractor and the agency eventually come to an agreement.

The selection of the contractor and the contractor's providers is based mostly on cost. The acceptance of the providers is negotiated based on preferences, rather than on objective evaluation.

The problem emerges during implementation and testing, when the agency first has access to the supplied systems and products. At that point, they are able to see things not visible during market research, and the difference between what they have bought and what they are receiving come into focus. Those differences exist because their product selection (or the contractor's selection) did not actually do what they needed it to do, and as acceptance testing wears on, the agency comes to understand their needs and requirements more clearly.

Only two possibilities exist for resolving unmet emerging requirements: Either the agency sets those requirements aside (and does without), or the contractor and providers exceed their expected costs by modifying their product. Usually, both of these occur, and the outcome for the agency is that the system is more expensive than expected and less useful than needed. Even if the agency succeeds in requiring the contractor to absorb those extra costs, it is difficult to say that the project is as successful as it could have been.

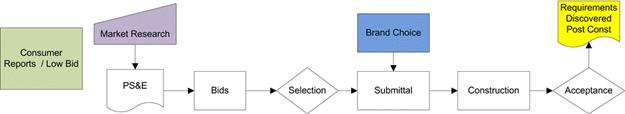

One might call this the “consumer reports” approach, where we make choices based on testimonials, short demonstrations, and advertising claims. The process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Consumer Reports acquisition approach

This process follows the traditional approach used for highway construction, and works reasonably well when all requirements are clearly understood and documented before the acquisition process begins. When requirements are not clearly understood, they will be discovered during the project, but after money has been spent and often too late to completely fulfill them.

Reducing Risk Using Requirements

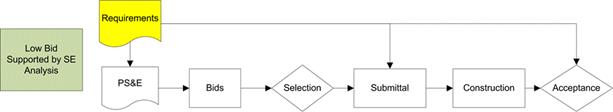

With well-documented requirements, the agency can still use the low-bid process. But the requirements have a specific effect at several key milestones of the project, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Low-bid process supported by requirements

Firstly, requirements developed before design can be used to evaluate design choices, and to provide a means by which the designer can know and demonstrate, by applying the Verification Plan to the design, that the design is complete and correct. This gives the agency a reason to have more confidence in the design documents.

Secondly, because the requirements will be included in the bid documents, the bidder has a basis for selecting technology and product providers. If a provider falls short later in the process, the contractor cannot claim that the requirements emerged after bidding, as is often the case with the first approach. This reduces the likelihood of the contractor making a poor choice and having to correct it at his expense during implementation.

Thirdly, the requirements give the agency a means of evaluating the materials submittal explicitly, without having to depend completely on brand reputation, testimonials, or sales activities. The agency should include a requirement in the Special Provisions governing the materials submittal, requiring the contractor to provide a detailed explanation of how the

proposed material supply will fulfill each requirement. This is, in essence, a pass through the Verification Plan. The agency can assess the materials submittal with much greater clarity and with much more leverage with the contractor if requirements are not fulfilled as expected.

Finally, the requirements provide a direct means of assessing work progress, and of determining when the system can be accepted.

Reducing Risk Further by Using Requirements for Selection

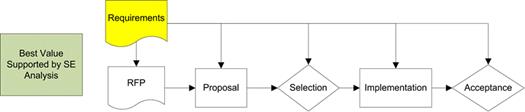

Agencies often believe that Federally-funded projects require a competitive-bid selection process. This is the case only for infrastructure construction, and does not apply to the acquisition of software systems. Software systems, like engineering services, can be acquired using a technical selection process based on a proposal. This process, when applied to Federal acquisitions, is called the Best Value approach because the selection of the most technically competent proposer provides the best value even if they do not have the lowest price. In most states, this process is the same as an engineering services acquisition, where cost is negotiated after making a technical selection. This process is shown in Figure 7, below.

Figure 7. RFP-based technical selection acquisition process

In this process, the documented requirements are included in the request for proposals (RFP). The instructions to the proposers request that they provide a detailed explanation of how their proposed approach fulfills each requirement. The RFP should include the Concept of Operations, the Requirements, and the Verification Plan. The proposal will then be the proposer's written verification of their proposed approach.

The agency can then select the system that most closely fulfills their most important requirements. Even when none of the proposers fulfills all the requirements, agencies are able to make a reasoned and informed selection based on their needs.

The benefit this process offers over the previous process is that agencies can verify requirements fulfillment as the basis for selection, rather than after selection. This minimizes the risk of choosing the wrong provider.

Sole-Source Acquisitions

According to Title 23 of the Code of Federal Regulation, Section 635, paragraph 411, federally- funded projects must be competitively acquired.

However, there are exceptions, which include:

- The State Department of Transportation (DOT) certifies that there is no competing product that meets the specification. In a requirements-led process, this can be demonstrated by providing a requirements analysis that shows that only one product fulfills all of the requirements. As with any certification, what is being certified must be evidenced in facts, not opinions or judgments.

- The State DOT certifies that the product is necessary for synchronization with existing installations. This is usually not appropriate for systems products that are the first such being acquired by an agency. However, there are cases where it does apply. Justification for synchronization will be easier if the system to which the new system must be compatible was competitively acquired using a requirements-driven process.

- The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) finds, on being presented with sufficient justification, that acquiring the technology is in the public interest even though there are other products or systems that also fulfill the requirements. These are known as public interest findings, and are in the public record, and must be carefully justified and evaluated.

- The acquisition is made for experimental purposes, on a small scale. The scale should be small enough so that if the experiment fails, it can be discarded without unreasonable loss, or without the loss exceeding the value of the resulting knowledge gained by the experiment. The agency should also provide an experimental plan identifying the gap in knowledge that the acquisition would fill, the way in which the acquisition will fill it, and the way in which the evaluation will be made to determine the results of the experiment. Generally, such experimental projects are used to help an agency understand what they will do with a new technology, to provide the necessary education to support a realistic concept of operations. Experiments should not be made to verify products (i.e., to determine that they fulfill requirements). That sort of experimentation should be done using a pilot project, as discussed in the next section.

Systems installed on an experimental basis should not be expanded to a full implementation using synchronization to justify a sole-source acquisition. Doing so circumvents the meaning of the regulation and may not withstand an audit. At some point, either technical or price competition will be required.

Services and Infrastructure

The RFP-based approach only works for software and services, and can only include hardware that is incidental to those acquisitions. For example, the computers on which the software runs will usually be considered incidental. However, physical infrastructure, including, for example, communications conduit and cable, pull boxes, traffic controller foundations and cabinet installations, and so on, must be competitively bid. Many Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) implementations include software, integration services, and infrastructure construction. For these projects, the best approach is to separate the software and services from the infrastructure construction, and contract them separately, using separate processes. The software and services can follow the RFP-based approach and the construction can be contracted by low bid.

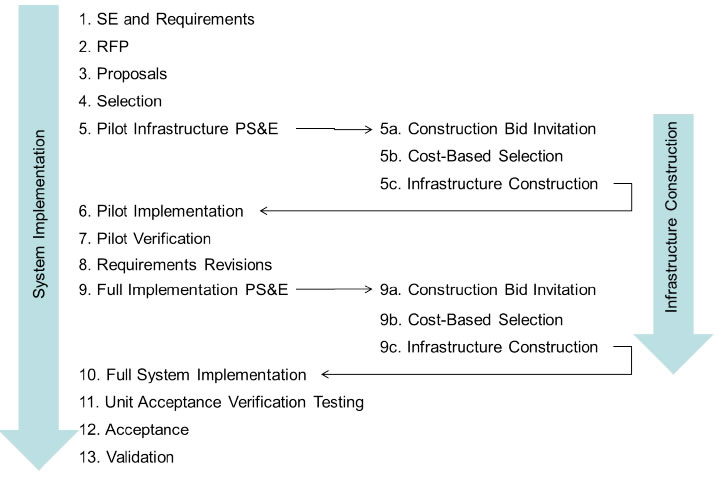

Figure 8 shows a complex project where systems services and infrastructure construction are divided into separate tracks. The project is further complicated by having a first pilot phase, which allows the agency to confirm that they fully understand their needs and requirements, and have documented them completely and correctly.

Figure 8. Complex project with both system services and infrastructure, and both pilot and full implementation phases

In this process, the concept of operations and requirements documents are completed, and then used as the basis for an RFP. The agency evaluates proposals and selects a system provider based on verification of the proposed approach against the requirements. The system provider then assists the agency in developing the design and specifications for the required physical infrastructure, which is then acquired using a conventional cost-based selection process.

The agency will verify the pilot phase of construction and system services against the requirements. In so doing, the agency will discover any deficiencies in the initial concept of operations and requirements documents, and will correct those documents as the basis for implementing the full system. The infrastructure component of the full system is then awarded to a contractor based on bid price. After implementation, the agency will verify final system against requirements, and once the implementation fulfills all requirements, the agency can accept it.

System providers usually have experience with acquisitions that separate services from infrastructure construction, and will build the cost of waiting for the completion of infrastructure construction into their negotiated price. The process should be fully identified in the initial RFP.