Organizing for TSMO

Case Study 5: Organization and Staffing - Organizing for TSMO

Chapter 1 - Introduction

Historically, transportation agencies have managed congestion primarily by funding major capital projects that focused on adding capacity to address physical constraints, such as bottlenecks. Operational improvements were typically an afterthought and considered after the new infrastructure was already added to the system. Given the changing transportation landscape that includes increased customer expectations, a better understanding of the sources of congestion, and constraints in resources, alternative approaches were needed. Transportation systems management and operations (TSMO) provides such an approach to overcome these challenges and address a broader range of congestion issues to improve overall system performance. With agencies needing to stretch transportation funding further and demand for reliable travel increasing, TSMO activities can help agencies maximize the use of available capacity and implement solutions with a high benefit-cost ratio. This approach supports agencies' abilities to address changing system demands and be flexible for a wide range of conditions.

Effective TSMO efforts require full integration within a transportation agency and should be supported by partner agencies. This can be achieved by identifying opportunities for improving processes, instituting data-driven decision-making, establishing proactive collaboration, and performing activities leading to development of performance optimization processes.

Through the second Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP2), a national partnership between the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and the Transportation Research Board, (TRB), a self-assessment framework was developed based on a model from the software industry. The SHRP2 program developed a framework for agencies to assess their critical processes and institutional arrangements through a capability maturity model (CMM). The CMM uses six dimensions of capability to allow agencies to self-assess their implementation of TSMO principles2:

- Business processes - planning, programming, and budgeting.

- Systems and technology - systems engineering, systems architecture standards, interoperability, and standardization.

- Performance measurement - measures definition, data acquisition, and utilization.

- Organization and workforce - programmatic status, organizational structure, staff development, recruitment, and retention.

- Culture - technical understanding, leadership, outreach, and program authority.

- Collaboration - relationships with public safety agencies, local governments, metropolitan planning organizations (MPO), and the private sector.

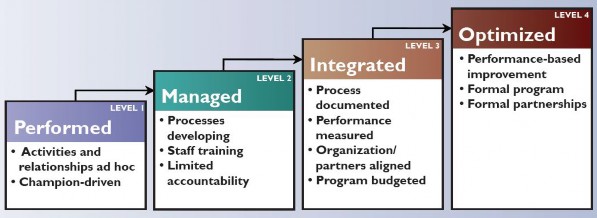

Within each capability dimension, there are four levels of maturity (performed, managed, integrated, and optimized), as shown in Figure 1. An agency uses the CMM self-assessment to identify their level of maturity in each dimension, to determine their strengths and weaknesses, and to determine actions they can take to improve their capabilities.

Figure 1. Chart. Four Levels of Maturity

Source: Creating an Effective Program to Advance Transportation System Management and Operations, FHWA Jan 2012

Figure 1. Chart. Four Levels of Maturity

Source: Creating an Effective Program to Advance Transportation System Management and Operations, FHWA Jan 2012

Purpose of Case Studies

In the first 10 years of implementation of the TSMO CMM, more than 50 States and regions used the tool to assess and improve their TSMO capabilities. With the many benefits experienced by these agencies, FHWA developed a series of case studies to showcase leading practices to assist other transportation professionals in advancing and mainstreaming TSMO into their agencies. The purposes of the case studies are to:

- Communicate the value of changing the culture and standard practices towards TSMO to stakeholders and decision-makers.

- Provide examples of best-practices and lessons learned by other State and local agencies during their adoption, implementation, and mainstreaming of TSMO.

These case studies support transportation agencies by showing a wide range of challenges, opportunities, and results to provide proof for the potential benefits of implementing TSMO. Each case study was identified to address challenges faced by TSMO professionals when implementing new or expanding existing practices in the agency and to provide lessons learned.

Identified Topics of Importance

The topic of systems and technology in TSMO is important because of the unique challenges associated with it, including collaborating among different departments and areas of expertise, planning and executing implementation, and managing systems and technology. The agencies highlighted for this case study addressed those challenges through consistent collaboration, integrated intelligent transportation systems (ITS) solutions, and employing data-driven decisions.

Interviews

Agencies were selected for each case study based on prior research indicating that the agency was excelling in particular TSMO capabilities. Care was taken to include a diversity of geographical locations and agency types (departments of transportation, cities, and MPOs) to develop case studies that other agencies could easily relate to and learn from. Interviews were conducted with selected agencies to collect information on the topic for each case study.

Description of Organization and Staffing

The organization and staffing component of TSMO planning addresses how the program will be delivered through institutional and organizational changes and includes:

- Program status.

- Organizational structure.

- Workforce capability.

- Staff development.

- Recruitment and retention.

Operational policies, procedures, and identification of roles and responsibilities for delivering the organization's TSMO mission must be defined and formalized in order to institutionalize a TSMO environment. Organizational change initiatives must have the full support of senior leadership and agency administration. Senior-level support and strategic goal setting promotes the value and focus of TSMO throughout the organization. Existing management strategies and structures are revised to address needs identified during strategic goal setting.

TSMO structures will vary by organization. There are many ways to structure TSMO and not all agencies will require major changes to existing organization and staffing. Agencies are encouraged to evaluate each possible solution and select the organizational structure that will work best with the desired outcomes for their TSMO program. Two example organizational structures are highlighted as follows: the Functional Organization and the Matrix Organization.

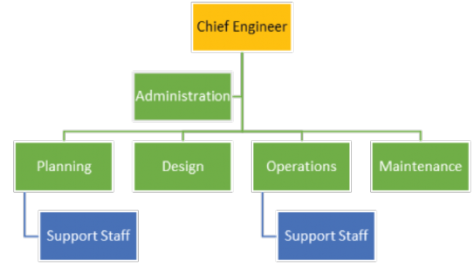

A functional organization, shown in Figure 2, is divided into several sub-units based on task or expertise. This is the most commonly known organizational structure and operates in a vertical hierarchy fashion. Members of each sub-unit report to a manager, who reports up through a chain of supervisors until the executive level is reached.

Figure 2. Chart. Example of a Functional Organizational Structure

Source: FHWA

Figure 2. Chart. Example of a Functional Organizational Structure

Source: FHWA

Table 1. TSMO Functional Organization Pros and Cons

| Pros |

Cons |

- Clear separation of functions or disciplines.

- Clear chain of command.

- Sub-units can work independently of others.

- Clear path for employee development.

- Easy to understand.

|

- Infrequent multi-discipline collaboration.

- Frequent ad-hoc tasks.

- Multiple sub-units do not always have the same mission.

- Atomistic.

- Resistant to change.

|

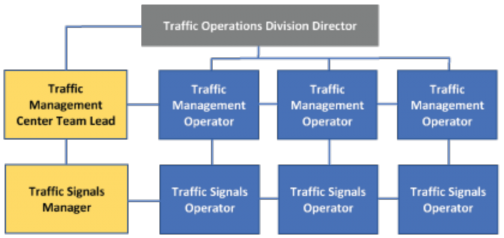

A matrix organization, shown in Figure 3, realizes that all daily tasks, challenges, and projects do not have a "one size fits all" method of practice. This organization operates both vertically and horizontally. As described in Project Management Quarterly, "The term 'matrix project organization' refers to a multidisciplinary team whose members are drawn from various line or functional units of the hierarchical organization. The organization so developed is temporary in nature, since it is built around the project or specific task to be done rather than on organizational functions.3"

Figure 3. Chart. Example of Matrix Organizational Structure

Source: FHWA

Figure 3. Chart. Example of Matrix Organizational Structure

Source: FHWA

Table 2. TSMO Matrix Organization Pros and Cons

| Pros |

Cons |

- Efficient use of resources.

- Increased flow of communication.

- Staff is spread throughout the organization.

- Lower staff turn-over.

- Project/program oriented.

|

- Typically, smaller projects.

- Not always a clear distinction in leadership.

- More complex structure.

- Difficulty sharing information with other organizational units.

- Varying guidance from multiple leaders.

|

For more information on TSMO Organization and Staffing, refer to https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop17017/ch6.htm.