Getting More by Working Together — Opportunities for Linking Planning and Operations2. Opportunities for Linking Planning and Operations2.7 Regional ITS ArchitectureBACKGROUND

A regional ITS architecture17 establishes a framework for implementing ITS projects at the regional level (see Exhibit 10). Because the development of the architecture is a Federal requirement,18 it presents a strong opportunity to enhance collaboration between a region's operations and planning practitioners. The development, use, and maintenance of a regional ITS architecture serves to highlight the importance of operations strategies that can improve transportation system performance, including strategies that address recurrent and non-recurrent congestion. The architecture can also help to ensure that these projects are included in the region's long-range plan and TIP. Because operations managers participate in development of the regional ITS architecture, they may work closely with transportation planners and are exposed to the region's planning and programming process. Planners who engage in the development of the regional ITS architecture will develop greater appreciation for the use of integrated communications and data technologies to enhance the efficiency of the transportation system. In addition, the architecture development process can highlight for planners the importance of integrating ITS technology and management considerations into regional plans. What Is a Regional ITS Architecture?ITS projects make use of electronics, communications, or information processing to improve the efficiency or safety of a surface transportation system. Such information technology is generally most effective when systems are integrated and interoperable. Recognizing this fact, the U.S. DOT has established the National ITS Architecture to provide a common structure for the design of ITS projects. The National Architecture describes what types of interfaces could exist between ITS components and how they will exchange information and work together to deliver ITS user service requirements. To implement ITS projects supported by the Highway Trust Fund, Federal regulations require that a region must develop a regional ITS architecture, using the National ITS Architecture as a resource.19 The purpose of developing a regional ITS architecture is to illustrate and document regional integration so that planning and deployment of ITS projects can take place in an organized and coordinated fashion.20 Once developed, any ITS project in the region that receives funding from the Highway Trust Fund must adhere to the regional ITS architecture. A region can be specified at a corridor, metropolitan, statewide, or multistate level, although the Metropolitan Planning Area is the minimum regional size within a metropolitan area. How Can the Regional ITS Architecture Create Stronger Linkages Between Planning and Operations?

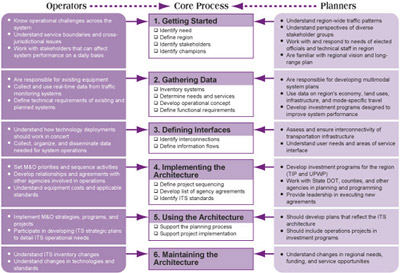

The regional ITS architecture serves as a focal point for coordination and collaboration between planning and operations practitioners. In a broad sense, the regional ITS architecture presents an accessible way for transportation planners to become more familiar with integrated management and operations activities and capabilities. It can also help to engage operations managers in regional planning, including establishing transportation investment priorities (see Case 36). Each of the discrete steps involved in the development, implementation, use, and maintenance of the regional ITS architecture provides opportunities for coordination and collaboration between planners and operators. In fact, the success of the regional architecture depends on planners and operators working together and bringing their expertise and perspective to bear throughout this process. Exhibit 11 illustrates some examples of these complementary perspectives as they relate to each step of the regional ITS architecture development process.21 These steps are reviewed in further detail after Exhibit 11.

Step 1 (Getting Started) in the development of the regional ITS architecture involves defining the stakeholders and people that will be involved, building consensus in the region, and establishing an overall plan for development (e.g., regional definition, timeframe, basic scope of services to be included). Operators bring to this process familiarity with operations stakeholders and potential leaders, and an understanding of service boundaries and areas of jurisdictional overlap. Planners bring experience working with diverse stakeholder groups and with elected officials, and ability to build regional consensus. Step 2 (Gathering Data) of the development process assembles an inventory of existing and planned ITS systems in the region, defines the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, and documents the ITS services to be provided and the functional requirements of each service. Operations practitioners are vital to this step because they bring a detailed understanding of existing ITS systems, particularly of systems that support interfaces that cross stakeholder boundaries. Operators also play a key role in identifying candidate ITS services that can address regional needs. Planners bring an understanding of the region's transportation needs, through detailed knowledge of the region's long-range plan and transportation investment programs. This perspective is critical to ensure that the architecture accounts for any new facilities or services planned for the region, and for the evolution of the system in general. Planners and operators then work together directly to discuss integration opportunities as part of the development of the operations concept and definition of system functional requirements. Step 3 (Defining Interfaces) identifies the interconnections between systems and defines the information flow between systems. As in Step 2, operations stakeholders bring to this process a unique understanding of ITS systems, including connection points and information flows. Through their efforts to collect, organize, and disseminate data on transportation system conditions, operators work daily with information flows within and between ITS systems. Because only a portion of the possible information exchanges suggested in the National ITS Architecture will be included as interconnects in the regional architecture, the planning perspective is useful to hone in on those that help support the needs (and corresponding services) of the region. Step 4 (Implementing the Architecture) defines several additional products that bridge the gap between the regional ITS architecture and regional ITS implementation. During the project sequencing step, operations experts are instrumental in identifying project elements that are dependent on other projects, estimating project costs, and identifying any regional ITS standards to be used in projects. Planners contribute an understanding of a region's existing short- and long-term project priorities and can assist with assessing ITS project benefits to the regional transportation system. Planning and operations stakeholders contribute to developing a list of agency agreements – operators because they typically maintain some existing agreements, and planners because they can provide leadership in the lengthy process of executing new agreements. Step 5 (Using the Architecture) is where the regional architecture directly supports the planning process, as spelled out in DOT's guidance. This occurs, for example, through increased stakeholder participation in the long-range plan development and through better system and inter-jurisdictional integration. The architecture can directly support the selection of projects for the TIP. The architecture can also serve as the basis for an ITS strategic plan and play a role in the development of corridor plans. Likewise, Step 6 (Maintaining the Architecture) provides further opportunity for planners and operators to participate in continuing forums to address ongoing operations priorities and integration opportunities. TAKING ADVANTAGE OF LINKAGE OPPORTUNITIESMost regions either have completed an initial ITS architecture or currently are in the process of developing one. These experiences have demonstrated a number of linkage opportunities, as discussed below. Designate the MPO to Lead the Development of the Regional ITS ArchitectureFederal regulations do not specify which agency should lead the development of a regional ITS architecture. In practice, a variety of agencies have taken the lead in different regions. At the regional scale, MPOs are ultimately responsible for ensuring that the regional ITS architecture requirements are met for the purpose of using Federal funds.

In regions where MPOs lead or are heavily involved in the development of the architecture, there is a strong opportunity for coordination with broader planning processes (see Case 37). MPOs often have expertise in collaborating with a broad set of stakeholders who can work toward solutions to regional transportation issues. Concurrently, MPOs can benefit from exposure to a process that focuses on management and operations strategies, since this may be unfamiliar territory for them. Given the authority that most MPOs have in regional transportation decisionmaking, they are in a unique position to ensure that the ITS architecture informs the transportation planning process. For example, data collection for planning purposes is not typically a high priority of operating agencies; the MPO can ensure that this need is recognized in the architecture. In addition, the MPO's experience with regional funding strategies allows it to inform stakeholders about funding opportunities or constraints during the course of developing the ITS architecture. Make the Regional ITS Architecture Part of an Integrated Regional PlanOnce a regional architecture is created, it is important that it serve as a resource for planning, programming, designing, and deploying ITS projects. The architecture should serve as a tool to improve regional thinking on operations. One way to promote the architecture's use is by incorporating it into the region's long-range transportation plan (see Case 38). This helps encourage consistency between proposed ITS projects and the architecture and ensures that additional integration opportunities are considered. Making the architecture part of the long-range plan also helps give operations managers a stake in the planning process. The architecture provides a point of entry to the broader planning effort, and allows operations managers to see how the ideas embodied in the architecture are framed within the context of the region's transportation policies, initiatives, and activities. Following are some steps that can begin to link the ITS architecture with the regional plan:

Link the Architecture to the TIP

Ultimately, the goal of the architecture is to facilitate the efficient deployment and use of ITS equipment, networks, and management structures to create a safer and more efficient transportation system. This requires prioritization of resources over a long period (see Case 39). U.S. DOT requires that the architecture includes a sequence of projects.23 Developing the sequence is a consensus building process that considers costs and benefits, technological feasibility, and project readiness. While not intended to be a formal ranking of ITS projects, the project sequence can be carried over to the TIP process. Both activities aim to use local knowledge and consensus-building to determine the most suitable sequence of projects to create a transportation network that best meets the region's needs. Some MPOs have connected the ITS architecture to the project development process by way of a checklist that is presented to all project sponsors (see Case 40). This is a simple and useful way to promote incorporation of consistent ITS elements into appropriate projects, particularly in areas where reference to the architecture tends to come late in the project development process. When project sponsors are prompted to consider ITS early in project development, ITS will be better integrated into projects and will be more likely to improve system efficiency. Consider developing a checklist for project sponsors that describes important ITS considerations. Build From the Architecture's Operational ConceptThe regional ITS architecture includes an operational concept that defines the institutional relationships among the organizations involved in the deployment and operation of regionally integrated ITS systems. Consider using this operational concept as a starting place for linking planning and operations more broadly. Consider how the operational concept can function to guide operations coordination beyond ITS. Build a Sustained Forum Around Maintenance of the ArchitectureA region's ITS priorities and organizational approach will need to evolve along with the region's travel patterns, available funding, and technological capabilities. Project implementation may also be a catalyst for maintenance of the architecture. As projects come into final stage of design the regional architecture should be reviewed to see if there is any impact to the capabilities documented in the regional architecture. Likewise, the architecture will need to respond to changes in the region's long-term goals and objectives. For these reasons, agencies should consider procedures and responsibilities for maintaining the regional ITS architecture as needs evolve within the region. The requirement to maintain the regional ITS architecture provides an opportunity to institutionalize certain planning and operations linkages. Without active engagement, stakeholder participation has a tendency to fall off when the architecture is complete. Agencies can identify activities to maintain involvement of a core group of stakeholders. Such a group can also serve to help coordinate transportation planning and operations more broadly. A good way to keep the stakeholder group active is to involve it in on-going regional transportation planning and programming activities. In addition, a number of regions have maintained engagement by designating a steering committee and by developing a regional ITS architecture Web site. Although a single agency may be designated to maintain the architecture, it is important that a diverse set of stakeholders remain actively engaged in the architecture review and maintenance processes. These groups of stakeholders can also function as ongoing forums where planning and operations practitioners ensure that their activities are coordinated. LESSONS LEARNEDWith many regions in the midst of ITS architecture development, there is a wealth of perspectives on how the process is working. Two lessons relating to planning and operations coordination have been expressed frequently. Stakeholders Take Interest in Concrete Benefits

A number of regions have labored to attract a diverse range of stakeholders to participate in the regional ITS architecture process. While coordinating ITS may already provide benefits to many planning and operations stakeholders, practitioners may not readily link these benefits with the more abstract architecture process. This challenge has been successfully addressed in several ways. Many regions have found that the architecture tends to attract more interest if it is promoted as a step to enhance existing successful ITS initiatives (see Case 41). This may be a traffic management center, an incident response program, or some other initiative that is particularly important to the stakeholders being targeted. Furthermore, to better engage stakeholders in developing the operations concept, real-world operations situations or scenarios can be used to guide the discussion and make the concept more accessible. Finally, all stakeholders take interest when funding is at stake. Greater participation has been achieved by highlighting the linkage between the ITS architecture and access to Federal funds, or by communicating ways that the architecture will delineate regional ITS investment priorities. The ITS Architecture Can Be Expected to Enhance Collaboration Over TimeFHWA's ITS architecture rule requires that the regional architecture be developed by April 8, 2005. After this deadline, Federal funds cannot be used for ITS projects in the region until a regional ITS architecture has been developed. Understandably, many regions that have not yet developed an architecture are focusing their attention on satisfying this Federal requirement. As a result, some of the more complex institutional issues are not being fully addressed in these initial regional architecture plans. Once the deadline is satisfied, regions that have recognized this value will have the opportunity to refocus on aspects of the architecture that help collaboration between jurisdictions and between ITS and regional planning processes. Ongoing implementation and maintenance of the architecture affords numerous opportunities to implement some of the collaboration opportunities that become apparent in the initial architecture development.

17 This section focuses primarily on regional ITS architectures. There are also statewide ITS architectures, and many of the same points may apply. The focus here is on the regional architecture because this is where the MPO role is likely to be greatest. 18 The Federal requirements related to ITS architectures apply for all regions wishing to receive Federal funds for ITS projects after April 2005. 19 23 CFR Part 940.3. 20 This is described in the FHWA rule and companion FTA policy published in January 2001 to implement Section 5206(e) of TEA-21. 21 See Regional ITS Architecture Guidance, U.S. DOT, October 2001, for a detailed description of these steps. 22 The best way to identify the status of your region's ITS architecture is through the State DOT or MPO. You can also check the following status Web site maintained by U.S. DOT's ITS Joint Programs Office http://www.its.dot.gov. 23 FHWA Rule 940.9(d)6 and FTA National ITS Architecture Policy Section 5.d.6.

|

| US DOT Home | FHWA Home | Operations Home | Disclaimer | ||